Why won't the NHS test for the heart attack gene 200,000 of us have?

Why won’t the NHS test for the heart attack gene 200,000 of us don’t even know we have?

- Familial hypercholesterolaemia, which raises cholesterol, is often symptomless

- If untreated, patients can die before reaching middle age, or even as children

- Experts say decision not to test all children is ‘breathtakingly short-sighted’

More than 200,000 Britons unknowingly carry a gene that puts them at high risk of a fatal heart attack or sudden stroke before they reach middle age, according to a pivotal study.

The inherited condition, in which a genetic fault causes cholesterol levels to rise alarmingly from birth, is often symptomless. If it is spotted, cholesterol-lowering medication, including statins, is highly effective at bringing problems under control.

However, if untreated, patients can, and do, die before they reach middle age. Some suffer heart attacks as children.

The new figures mean inherited high cholesterol – familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) – becomes one of the most common genetic conditions in the UK.

Experts and campaigners hit out at the ‘breathtakingly short-sighted’ decision by the Government’s UK National Screening Committee not to test all children for FH alongside other hereditary illnesses.

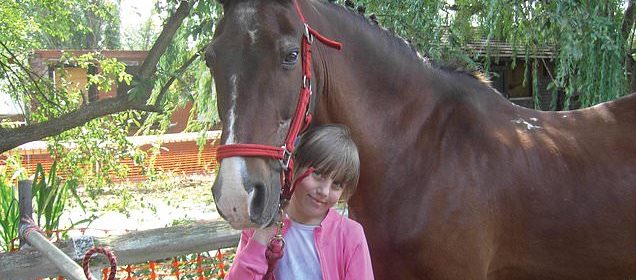

Proof of the devastating effects of genetic high cholesterol can be found in the tragic story of Rianna Wingett, pictured. In November 2009, the 11-year-old collapsed seconds after finishing a cross-country run on playing fields at her school in Hornchurch, Essexz. As she suffered a huge, fatal heart attack, she turned to a friend and said: ‘I think I’m going to die’

The committee began considering screening children for FH in 2016, and rejected it two years later. Campaigning charity Heart UK appealed. However, in April it was told screening had been rejected again as a question mark still hung over the right age to offer a test.

Fault causes a heart attack every day

Cholesterol is a fat made by the liver and is essential for a range of processes such as building cell walls.

But if too much is in the blood, it contributes to the formation of inflamed ‘spots’ known as plaques inside artery walls.

These plaques can rupture and trigger the formation of blood clots which then break away and travel through the circulation, risking heart attack or stroke.

In those with familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH), a fault in at least three genes can affect ways in which the body processes cholesterol, leading to high levels in the blood.

There is a 50:50 chance the genetic fault will be passed from a parent to a child.

Studies have shown the risk of heart disease is up to 13 times higher in people with untreated FH.

About one person with FH has a heart attack every day in the UK, and a third do not survive.

This was despite a 10,000-patient study finding that testing between the ages of one and two was effective in picking up the condition. ‘It’s an absolute disgrace,’ said Heart UK chief executive Jules Payne. ‘Heart experts around the world agree that testing children should be routine. The committee got it totally wrong and disregarded the evidence.

‘FH can be picked up with a simple finger-prick cholesterol test and cheek swab between the ages of one and two, at the same time as babies have a number of other routine check-ups and vaccinations. As it stands, adults and children are needlessly dying when we have effective preventative treatment.’

Proof of the devastating effects of genetic high cholesterol can be found in the tragic story of Rianna Wingett.

In November 2009, the 11-year-old collapsed seconds after finishing a cross-country run on playing fields at her school in Hornchurch, Essex.

As she suffered a huge, fatal heart attack, she turned to a friend and said: ‘I think I’m going to die.’

A post-mortem revealed that one of the main arteries to her heart was so clogged with cholesterol that the gap left for blood to flow through was no bigger than a pinprick.

Leyton Cooper also carried the genetic fault. The company manager was just 35 when he had a massive heart attack in September 2012. He was found on the floor of his home in Oldham, near Manchester and died in hospital. Despite being slim and healthy, a major heart artery was found to be blocked with fatty plaques.

In the largest study of its kind, which was published last week in the journal Circulation, experts examined data from seven million medical records and found a shocking one in 300 children and adults had signs of FH – making it almost twice as common as previously thought.

The researchers looked for mention in the records of higher-than-expected cholesterol readings, heart disease in young patients and other telltale signs of FH – fatty cholesterol can accumulate in lumps under the skin and inside the eye, causing a visible white ring around the iris, for instance.

They used this data to create a scoring system that could determine the true number of people who carried the gene. The new figures suggest that about 220,000 Britons have FH – yet, at present, just 20,000 have been diagnosed.

GPs spot the condition, or suspect it, in a number of ways including if a person has a suspiciously high total cholesterol above 7.5 or a family history of early heart disease.

If children are found to have FH, they are offered lifestyle advice including avoiding cholesterol-raising high-fat foods, pictured

When there is a very strong likelihood that a patient has the condition, they should be offered a genetic test to give a definitive diagnosis. As FH can be passed down through just one parent, other family members are also offered a gene check in a process known as cascade testing.

At present, if children are found to have FH, they are offered lifestyle advice including avoiding cholesterol-raising high-fat foods and staying active.

Both of these measures can control levels of a type of cholesterol called LDL, which is known to be involved in the damage inside arteries that leads to cardiovascular disease.

As levels rise, usually by the age of nine, they are offered cholesterol-lowering statin medication.

The system of cascade testing typically begins with an adult in the family being picked up, often because they have developed angina – chest pain – or suffered a heart attack or stroke.

However, as Professor Kausik Ray, the Imperial College London cardiologist who co-authored the latest research, explains: ‘By this time, you are firefighting. These patients will have been running high cholesterol levels since birth and have missed out on decades of treatment. We need to find a better way of identifying them.’

The benefits of treating FH from childhood are clear. In one major study, published last year, researchers followed youngsters with the condition who had been given statins for 20 years.

Their incidence of cardiovascular disease was then compared with their parents, who also had the condition. Just one per cent of the children – who by the end of the study were aged 39 – had suffered a major heart event.In the parent group, a quarter had been hit by a heart attack or stroke by this age, and one in 20 had died.

‘With kids, we can give advice to eat healthily, to not put on weight and not smoke, and they can keep this up for life, alongside medication,’ says Prof Ray. ‘This hugely reduces the risk of illness and death and means we could offer children today born with FH a normal life expectancy.

‘Given what we know, to decide not to test them seems breathtakingly short-sighted.’

Source: Read Full Article