The Next Vaccine Challenge: Reassuring Older Americans

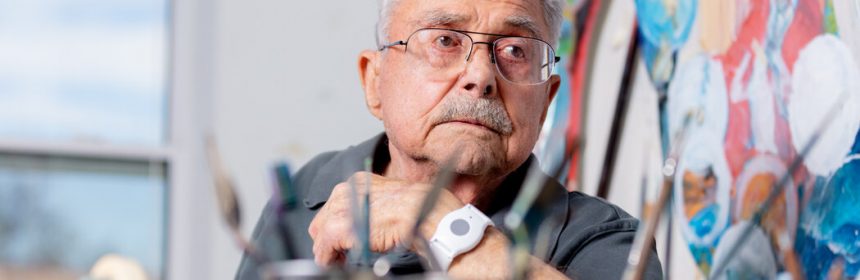

He can barely see or hear, but 95-year-old Frank Bruno lives on his own terms: alone, unafraid and now — thanks to the coronavirus vaccine — “ironclad,” as he describes it.

Mr. Bruno, an artist and World War II veteran, volunteered for the Moderna clinical trial only because his nephew was doing so. He thought he may have received the vaccine and not a placebo because he had some mild side effects; he became certain after he tested positive for antibodies.

He was delighted with the freedom the shot afforded him. He needed to have his shower fixed and wanted to see his nephew; he felt able to do both without fear of the virus.

As for side effects? “I’ve had mosquito bites bothered me worse than that,” he said. “I just can’t understand why people are afraid.”

Mr. Bruno and older Americans like him are pivotal to the success of the vaccination campaign now rolling out across the United States. Members of his age group are the most likely to be hospitalized and to die from Covid-19, and the least likely to muster a strong immune response to the coronavirus.

In some states, nearly 40 percent of deaths from Covid-19 have occurred among residents of nursing homes. That’s why an advisory committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine be given first to the nearly three million residents of long-term-care homes.

But one member of the committee, Dr. Helen “Keipp” Talbot, voted against the recommendation, saying that the vaccines had not been tested enough in frail populations and that bad medical outcomes coinciding with the immunization — common in that age group — could undermine public confidence in the new vaccine. (Dr. Talbot declined to be interviewed for this article.)

But other experts on the committee said all available evidence indicated the vaccine is safe and effective for nursing home residents and older Americans generally.

“The vaccine seems to be performing as well as one would like, even in very old populations,” said Dr. Stanley Perlman, an immunologist at the University of Iowa and a member of vaccine advisory committees of both the C.D.C. and the Food and Drug Administration.

“There’s nothing to say it won’t be safe,” he added.

There was some reason for scientists to wonder whether a coronavirus vaccine might not work as well in the elderly. As people age, bodily defenses against pathogens weaken, and the response to vaccines also falters.

The drug makers Sanofi and GlaxoSmithKline said on Friday that their vaccine seemed not to work well in older people, because the dosage was too low to generate a sufficient immune response in that population.

“For many, the immune response can sometimes be diminished or dampened or delayed,” said Dr. Sharon Inouye, a geriatrician at Harvard Medical School.

Scientists have devised workarounds by overloading vaccines with the viral proteins that provoke an immune response, or turbocharging them with adjuvants — chemicals that strengthen the immune response.

“That’s why the shingles vaccine has twice as much antigen as the chickenpox vaccine,” Dr. Perlman said.

Pfizer and Moderna did not provide statistics regarding their vaccines’ effectiveness in people over age 80, but the data do show the vaccines have performed well in all volunteers over age 65.

Dr. Timothy Farrell, a geriatrician at the University of Utah, said he was surprised but thrilled by the vaccines’ effectiveness in this group. “It’s going to be very important to see the subgroup analysis,” he said — that is, to learn whether there are significant differences after age 85.

Even so, he has been recommending the vaccine to all of his patients, who range in age from 65 to 106 years old.

“We have a clear and present danger of Covid, and we have social isolation,” Dr. Farrell said. “We know that that’s an independent risk factor for mortality, even stronger than individual chronic diseases.”

Dr. Inouye also arrived at the same conclusion, both professionally and personally.

Her 91-year-old mother, who lives in an assisted living facility, is independent and spry, still playing piano and bridge and exercising regularly. Still, her mother’s age, medical condition and living situation put her at “very, very, very high risk for Covid,” Dr. Inouye said.

“We’re just desperately worried about her every single day,” she added. “When you balance that tremendous fear, I just think the risk for her of getting Covid is so much higher than the risk of a side effect, which we know is going to be very rare.”

The Road to a Coronavirus Vaccine ›

Answers to Your Vaccine Questions

With distribution of a coronavirus vaccine beginning in the U.S., here are answers to some questions you may be wondering about:

-

- If I live in the U.S., when can I get the vaccine? While the exact order of vaccine recipients may vary by state, most will likely put medical workers and residents of long-term care facilities first. If you want to understand how this decision is getting made, this article will help.

- When can I return to normal life after being vaccinated? Life will return to normal only when society as a whole gains enough protection against the coronavirus. Once countries authorize a vaccine, they’ll only be able to vaccinate a few percent of their citizens at most in the first couple months. The unvaccinated majority will still remain vulnerable to getting infected. A growing number of coronavirus vaccines are showing robust protection against becoming sick. But it’s also possible for people to spread the virus without even knowing they’re infected because they experience only mild symptoms or none at all. Scientists don’t yet know if the vaccines also block the transmission of the coronavirus. So for the time being, even vaccinated people will need to wear masks, avoid indoor crowds, and so on. Once enough people get vaccinated, it will become very difficult for the coronavirus to find vulnerable people to infect. Depending on how quickly we as a society achieve that goal, life might start approaching something like normal by the fall 2021.

- If I’ve been vaccinated, do I still need to wear a mask? Yes, but not forever. The two vaccines that will potentially get authorized this month clearly protect people from getting sick with Covid-19. But the clinical trials that delivered these results were not designed to determine whether vaccinated people could still spread the coronavirus without developing symptoms. That remains a possibility. We know that people who are naturally infected by the coronavirus can spread it while they’re not experiencing any cough or other symptoms. Researchers will be intensely studying this question as the vaccines roll out. In the meantime, even vaccinated people will need to think of themselves as possible spreaders.

- Will it hurt? What are the side effects? The Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine is delivered as a shot in the arm, like other typical vaccines. The injection won’t be any different from ones you’ve gotten before. Tens of thousands of people have already received the vaccines, and none of them have reported any serious health problems. But some of them have felt short-lived discomfort, including aches and flu-like symptoms that typically last a day. It’s possible that people may need to plan to take a day off work or school after the second shot. While these experiences aren’t pleasant, they are a good sign: they are the result of your own immune system encountering the vaccine and mounting a potent response that will provide long-lasting immunity.

- Will mRNA vaccines change my genes? No. The vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer use a genetic molecule to prime the immune system. That molecule, known as mRNA, is eventually destroyed by the body. The mRNA is packaged in an oily bubble that can fuse to a cell, allowing the molecule to slip in. The cell uses the mRNA to make proteins from the coronavirus, which can stimulate the immune system. At any moment, each of our cells may contain hundreds of thousands of mRNA molecules, which they produce in order to make proteins of their own. Once those proteins are made, our cells then shred the mRNA with special enzymes. The mRNA molecules our cells make can only survive a matter of minutes. The mRNA in vaccines is engineered to withstand the cell’s enzymes a bit longer, so that the cells can make extra virus proteins and prompt a stronger immune response. But the mRNA can only last for a few days at most before they are destroyed.

Source: Read Full Article