Research shows how self-injectable contraception can enable women to take charge of their reproductive health

Allen Namagembe is a clinical epidemiologist, a biostatistician, and a global expert on self-injection. She is the Uganda Deputy Project Director and M&E Lead on the Uganda Self-Injection Scale-Up project at PATH. Dr. Jane Cover is a Research and Evaluation Manager on PATH’s Sexual and Reproductive Health team and the PATH-JSI DMPA-SC Access Collaborative.

Now, they explain their team’s two studies, published in Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, where they used a human-centered design approach to develop and implement a pilot self-injection program in Uganda. Their results show how the program can increase women’s contraceptive access and options.

For some, the term “self-care” might conjure up images of skincare routines, bubble baths, and meditation. But in public health, self-care refers to the ability of individuals to self-manage aspects of their health care with the goal of promoting and sustaining health, preventing disease, and managing illness or disability. Grounded in evidence, agency, and equity, self-care interventions are key components of a holistic primary health care system and can help fill gaps in access to essential health services.

We both conduct research in the sexual and reproductive health field not just because of our love of science, but because ultimately, we hope to enable women and girls to make informed choices about what works best for them—self-care interventions are one way to achieve that.

Contraceptive self-injection is feasible and effective

Self-injectable contraception is a self-care intervention that has shown immense potential in improving women’s access to high-quality family planning services.

For more than 10 years, PATH has collaborated with ministries of health and partners to research, introduce, and scale up subcutaneous DMPA (DMPA-SC, subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate), an innovative, easy-to-use contraceptive that can be injected by any trained individual, including women themselves, in a location and at a time that works best for them. Currently, DMPA-SC is available in more than 55 countries, more than 35 of which offer self-injection.

The simplicity, privacy, and convenience of self-injected DMPA-SC can help reduce burdens on the health care system by expanding who can administer contraception and when. This has enormous implications for women and adolescent girls who have the right to choose whether, and when they get pregnant, and what kind of contraception, if any, they use.

Research by PATH and our partners has shown that self-injected contraception is both feasible and effective. Findings from our team’s two recently published studies in Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, which are among the first to evaluate a self-injection program under routine conditions outside of a research setting, provide further evidence to support this.

Women can self-inject successfully with training and support

We used a human-centered design approach to develop and implement a pilot self-injection program in Uganda, working closely with the Ministry of Health to integrate this option in both the private and public sector. Trained providers offered DMPA-SC as a voluntary contraceptive method at participating facilities in three districts. We then assessed the experiences of women, adolescent girls, and health workers who participated in the program and evaluated the effectiveness of different program designs, generating evidence to inform the rollout of future self-injection programs.

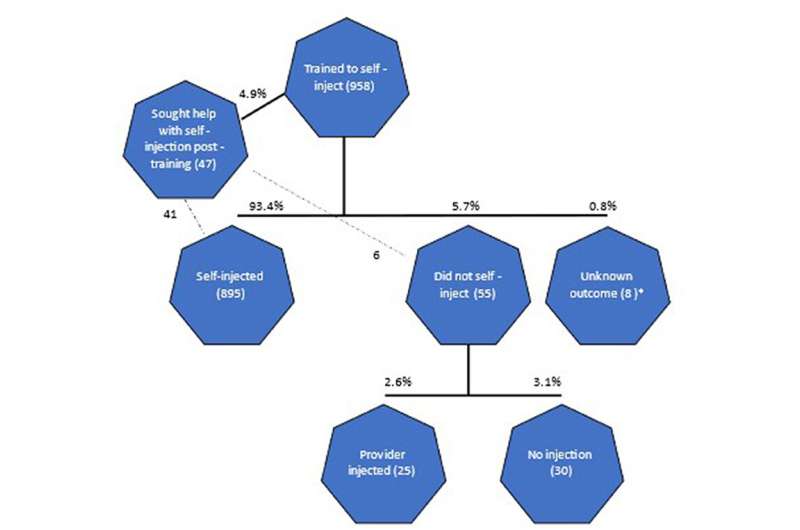

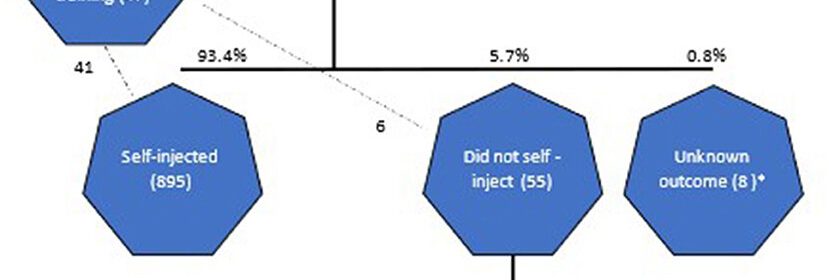

Within the first year, 4,340 women voluntarily opted for self-injection. Out of the 958 self-injection clients we interviewed, 93% were able to self-inject independently at home after receiving a single training session—and the majority (69%) continued self-injection for at least one year. These results reflect clients’ satisfaction with self-injection and echo the high self-injection continuation rates found in research settings.

On the flip side, a substantial share of women who expressed interest in self-injection and received training opted not to self-inject, with most citing fear or lack of confidence as the main barrier. Their decision is an important reminder that training quality influences self-injection uptake, and that even with high-quality training, self-injection is not for everyone—and that’s okay.

We learned that single women, women who have partners that are supportive of family planning, those who trained with a job aid or an injection demonstration, and those who received individualized training were more likely to opt for self-injection than their counterparts.

Another key outcome was that, regardless of education level, women were able to self-inject successfully with appropriate training and support. This is an important finding, as women without education may face discrimination in accessing self-injection services despite standing to benefit the most due to the barriers they face in accessing family planning services.

Health workers play a crucial role in self-care

Clients’ access to self-care can hinge on the perspectives of health workers, who often serve as gatekeepers to self-care interventions. Through interviews with 120 health workers active in the self-injection program, we found that most were very satisfied with the program and reported that it was moderately easy to integrate self-injection training into their workload.

While having clients self-inject can ultimately reduce health workers’ workload, training clients on self-injection can be challenging and time-consuming. Health workers reported obstacles such as lack of time to train clients in the clinic setting, lack of materials among community health workers, and client fear of self-injection. However, community health workers were less likely than clinic-based health workers to report time challenges and indicated higher levels of satisfaction and ease in offering self-injection services.

Government leadership makes all the difference

Source: Read Full Article