Firing Up the Neural Symphony

The research on brain stimulation is advancing so quickly, and the findings are so puzzling, that a reader might feel tempted to simply pre-order a genius cap from Amazon, to make sense of it all later.

In just the past month, scientists reported enhancing the working memory of older people, using electric current passed through a skullcap, and restoring some cognitive function in a brain-damaged woman, using implanted electrodes. Most recently, the Food and Drug Administration approved a smartphone-size stimulator intended to alleviate attention-deficit problems by delivering electric current through a patch placed on the forehead.

Last year, another group of scientists announced that they, too, had created a brain implant that boosts memory storage. All the while, a do-it-yourself subculture continues to grow, of people who are experimenting with placing electrodes in their skulls or foreheads for brain “tuning.”

Predicting where all these efforts are headed, and how and when they might converge in a grand methodology, is an exercise in rank speculation. Neuro-stimulation covers too many different techniques, for various applications and of varying quality. About the only certainties are the usual ones: that a genius cap won’t arrive anytime soon, and that any brain-zapping gizmo that provides real benefit also is likely to come with risk.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

Nevertheless, the field is worth watching because it hints at some elementary properties of brain function. Unlike psychiatric drugs, or psychotherapy, pulses of current can change people’s behavior very quickly, and reliably. Turn the current on and things happen; turn it off and the effect stops or tapers.

To begin to appreciate the latest science, it helps to have a working picture of the brain’s electrical system — a metaphor. Metaphors can be dicey when applied to the brain; they’re inherently inadequate by nature, and choosing one risks endorsing an intervention, including brain stimulation, with unknown risks.

An orchestra metaphor is a good place to start. A brain humming along well is a Mozart-like production, with many diverse, specialized neural instruments synchronizing with each other to create a sense of unity.

“In conducting, in each moment, you’re working to coordinate all instruments to play in the same tempo, with the same intensity,” said James Conlon, music director of the Los Angeles Opera and principal conductor of the RAI National Symphony Orchestra in Torino, in a phone interview. “I continually switch between listening, leading and following: back and forth and back, approving the sound, receiving or making adjustments.”

Brain scientists often liken brain function to a symphony. “If you watch an orchestra perform, once the performance starts, the cello player is looking at the person next to him, or her, not the conductor,” said Michael Gazzaniga, a psychologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “The same thing is likely happening in the brain. The question for me is, does the brain have a conductor.”

The crudest form of electrical intervention is electroconvulsive therapy, or E.C.T., which sends a seizure-inducing current through the brain, providing at least temporary relief to some people with severe depression. Doctors have used E.C.T. for nearly a century, although the treatment remains controversial for many patients. Metaphorically speaking, E.C.T. is akin to halting the orchestra’s performance and sending the musicians , from oboe to timpani, home to get some rest and come back tomorrow refreshed.

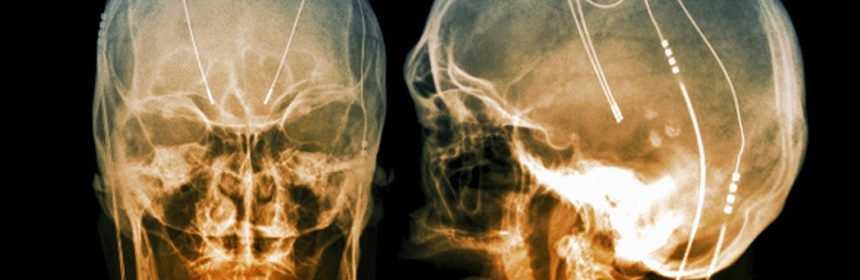

A more targeted form of electrical therapy, called deep brain stimulation, or D.B.S., has been used to manage conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy. In D.B.S., an electrode is threaded into a specific area of the brain that is being disruptive; stimulating it, paradoxically, knocks out activity in that specific region.

If a particularly strong section is off-key, “it can affect the entire system, and the whole orchestra sounds off,” said Dr. Helen Mayberg, director of the Center for Advanced Circuit Therapeutics at Mt. Sinai’s medical school; she has developed D.B.S. strategies for severe depression. “You can think of it as firing everyone in that section” — sending the percussion home permanently — Dr. Mayberg said. “Precision is absolutely critical.”.

The recent brain-stimulation studies employ a technique distinct from either E.C.T. or D.B.S., but which still can be understood in terms of an orchestra. In one of the studies, scientists at Boston University found that they could improve working memory in older adults by optimizing what’s called rhythmic “coupling” between frontal and temporal cortex areas in a person’s brain.

In the brain, the activities of distant regions coordinate by means of low-frequency theta waves. The researchers used electric stimulation, delivered through a skullcap, to amplify these waves, enhancing coordination between the two brain regions and, in older adults, improving working memory.

“We think what we’re doing is essentially synchronizing these two separated areas,” said Robert M.G. Reinhart, a neuroscientist at Boston University and one of the authors of that study. In effect, the stimulation acts as an orchestra conductor, listening, synthesizing and leading.

In another recent study, a team of brain scientists found that they could blunt or reverse symptoms of fatigue, poor concentration and mental fogginess in a woman who had suffered a severe brain injury in a car accident 18 years earlier. They did so by providing steady current, during waking hours, through two electrodes implanted on either side of the thalamus, a deep brain region often described as a central switching center of the brain. Metaphorically, they turned up the volume — or, perhaps, they had the conductor clap her hands and fix a hard stare on the musicians.

Of course, a metaphor is just a metaphor, and only one step toward decoding the intimate mystery of consciousness. But in this age of technological onslaught, of ever higher-tech therapies and claims small and large, better to have some guide to the mind in mind than none at all.

Benedict Carey has been a science reporter for The Times since 2004. He has also written three books, “How We Learn” about the cognitive science of learning; “Poison Most Vial” and “Island of the Unknowns,” science mysteries for middle schoolers.

Source: Read Full Article