Examination, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Piriformis Syndrome

Piriformis syndrome is often characterized by pain and numbness in the buttocks and leg. At the German Pain and Palliative Day 2022, Heinrich Binsfeld, MD, vice president of the German Society for Pain Medicine, and physiotherapist Matthias Oeding reviewed the disease pattern’s most important characteristics. They discussed pitfalls that should be noted during diagnosis and how to treat the syndrome.

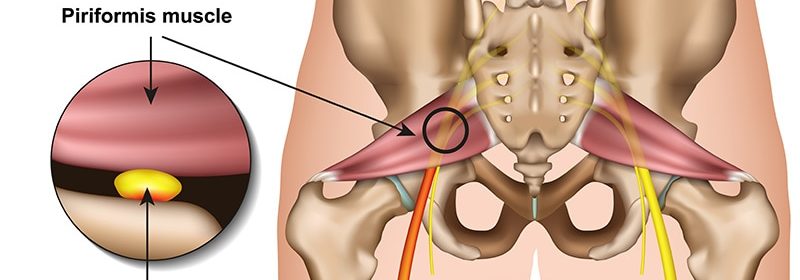

Sciatic Nerve Compression

The piriformis muscle is a flat, pyramidal to pear-shaped skeletal muscle of the hip musculature. It runs from the outer edge of the sacrum to the greater trochanter of the thigh. Piriformis syndrome is caused by this muscle compressing the sciatic nerve.

Sciatic Nerve Variations

The sciatic nerve is a peripheral nerve of the lumbosacral plexus. In humans, it originates from the last two lumbar and first three sacral vertebral segments L4-S3. When viewed in more detail, the sciatic nerve (in humans) is actually two nerves (the fibular or common peroneal nerve and the tibial nerve), which control different muscles and only appear to be a single nerve due to the connective tissue-like shell.

The sciatic nerve can emerge completely below or completely above the piriformis muscle. An early division is also possible, where one part of the nerve pulls through the muscle and the other does not. There are variants that run both above and below the piriformis muscle at the same time or that pull through the piriformis muscle completely. This wide variety makes the therapeutic approach more difficult. An ultrasound can help to detect the route of the nerve and treat the muscle accordingly without damaging the nerve.

Physical Examination and Tests

By using muscle tests, piriformis syndrome can be differentiated from other causes. In a stretched hip, the piriformis muscle acts as an external rotator; in a flexed hip, it acts as an abductor. If testing these functions causes any pain, this indicates piriformis syndrome. The external rotation test is performed in a seated position. The following tests confirm the diagnosis:

-

Mirkin test: Pressure on the buttocks where the sciatic nerve crosses the piriformis muscle while the patient slowly bends toward the ground.

-

Pace test: Abduction of the affected leg while seated.

-

Beatty test: Lifting the knee on the unaffected side several centimeters while supine.

-

Oeding test: Abduction of the affected leg while supine.

-

Freiberg test: Pain on forceful internal rotation of the flexed thigh.

Differential Diagnoses

When examining the hip joint, Oeding looks for the following signs:

-

Arthrosis/arthritis of the hip joint (internal rotation more severely restricted than extension).

-

Insertional tendonitis (through testing of isometric resistances).

-

Bursitis through palpation around the greater trochanter; several bursae are found here (primarily the trochanteric bursa; Oeding also recommends palpating in dorsal and caudal directions).

-

Checking for muscle shortenings in the iliopsoas muscle, rectus femoris muscle, and tensor fasciae latae muscle.

-

Meralgia paresthetica.

Meralgia Paresthetica

Meralgia paresthetica is a nerve-compression syndrome of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve in the region of the inguinal ligament. The nerve originates from the lumbar plexus, leaves the pelvis close to the anterior superior iliac spine, and penetrates the fibers of the inguinal ligament, where it can easily be constricted and is referred to as inguinal tunnel syndrome.

If the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is disrupted, this leads to sensory deficits across the anterior lateral side of the thigh. Unlike a radiculopathy, this does not lead to motor-function loss.

The cause of meralgia paresthetica is often mechanical pressure under the inguinal ligament or also push or pull effects along the nerve, especially at the pelvic exit point. A nerve lesion as a complication of medical measures is also not uncommon.

Nocturnal Pain, Sensory Deficits

Binsfeld summarized the main symptoms as follows:

-

Pinprick-like, burning pain at the anterior external side of the thigh.

-

Pain in the hip joint primarily during extension (ie, when walking and standing).

-

Sensory disturbances on the external side of the thigh.

-

Pain during the night.

-

Sensory deficits also in the area surrounding the anterior side of the thigh.

Typically, discomfort improves when flexing the hip and is provoked through hyperextension of the hip joint with simultaneous bending of the knee. In two thirds of those affected, there is a painful spot almost medial to the superior anterior iliac spine.

Later, autonomic nervous system disorders develop (eg, hypotrichosis in the innervation area and thinning of the skin). Sensitivity worsens at an increasing rate and can eventually remain permanently disrupted, although the discomfort continues.

NSARs and Surgery

Doctors should inform those affected about the mostly harmless cause of their severe pain and sensory disturbances. Simple measures such as avoiding long periods of standing or repeated hip extension can alleviate symptoms. Excess weight should be reduced.

Nonsteroidal antirheumatics (NSARs) can be used first to attempt to address the pain. Nerve blockade with a local anesthetic or steroid in the primary indication does not just alleviate the acute pain but can also lead to lasting freedom from the symptoms, according to Binsfeld. In severe cases, an operation to release the nerve from the tissue exerting pressure (neurolysis) must be considered. In some cases, the surgical widening of the nerve tunnel through the inguinal ligament is necessary.

Movement Patterns and Stretching

Patients should temporarily avoid activities that trigger the pain. Special stretching exercises for the posterior musculature of the hip and piriformis muscle, as well as corticosteroid injections, may help. NSARs may also temporarily alleviate the pain. Surgical intervention is rarely justified.

Binsfeld also advised that in addition to the therapeutic procedures mentioned, the effect of physical therapy should not be overlooked.

|

Pain in the Thigh, Not Always Just in the Back In addition to pure joint pain (hip, knee), extensive stripes of pain in the thigh are common symptoms for many patients in general, neurological, orthopedic, and pain-therapy practices and outpatient clinics. As a general rule, it is not so difficult to also find the local cause clinically with a high degree of probability using medical history information on pain localization, possible sensorimotor deficits, and examination findings. If not all of the information and findings are in-line with a lumbosacral radiculopathy, and imaging (CT, MRI) also does more to confirm than remove doubts, it is good to know some differential diagnoses that are not so rare. The typical “sciatica symptoms” are rarely damage to the sciatic nerve but are rather proximal compression damage to the radix at L5 and, in particular, S1. With piriformis syndrome, however, the sciatic nerve itself is irritated by a shortened and hypertrophied piriformis muscle in the dorsal pelvis. This is fostered by anatomical variations in which the sciatic nerve does not pull laterally past but rather wholly or partly through the belly of the piriformis muscle. Typically, pseudoradicular pain and, depending on intensity, dysesthesia, develop gluteally on the back of the thigh and lower leg, sometimes extending to the sole or back of the foot, and are confusingly similar to the dermatome localizations of L5 and, in particular, S1. In a flexed hip, the piriformis muscle functions as an abductor; in a stretched hip, it acts as an external rotator. The pain becomes more intense during forceful hip abduction with a flexed hip and during external rotation with a stretched hip. In addition, hyperextensions may provoke the pain. The asymmetry of the piriformis muscles when compared side-by-side can best be detected using MRI. Ultrasound examinations of the proximal sciatic nerve are often unsuccessful because the nerve no longer passes sufficiently close to the surface there. Presumed causes of piriformis syndrome are extended periods of sitting on one side or asymmetrical stresses such as sitting with a wallet in the back pocket. In terms of therapy, physical therapeutic measures are helpful above all. Botulinum toxin injections can also be helpful for persistent symptoms. Pain and dysesthesia in the distal anterior and external sides of the thigh can develop through irritations to the radix at L3, but also through compression of the clearly sensitive lateral femoral cutaneous nerve on the lateral inguinal ligament at the level of the superior anterior iliac spine. Burning pains with or without hypesthesia are labeled as meralgia paresthetica (inguinal tunnel syndrome). The symptoms are intensified through increased abdominal pressure (obesity, advanced pregnancy) on the nerve when standing and walking or through external local pressure, eg, from belts on pants or backpacks that are too tight). Stretching in the hip joint intensifies the symptoms, and so symptoms often occur at night when supine. Local space-occupying masses such as hernias or lipomas should be ruled out. In addition to the local release of pressure, pain-modulating substances such as gabapentin or pregabalin are often helpful. Local injections (anesthetics, steroids) often only alleviate the pain for a limited time. The rate of spontaneous recovery over 12 to 18 months is relatively high. For persistent pain, surgical neurolysis should be performed. |

This article was translated from Coliquio.

Source: Read Full Article