Elimination of human African trypanosomiasis within reach, study finds

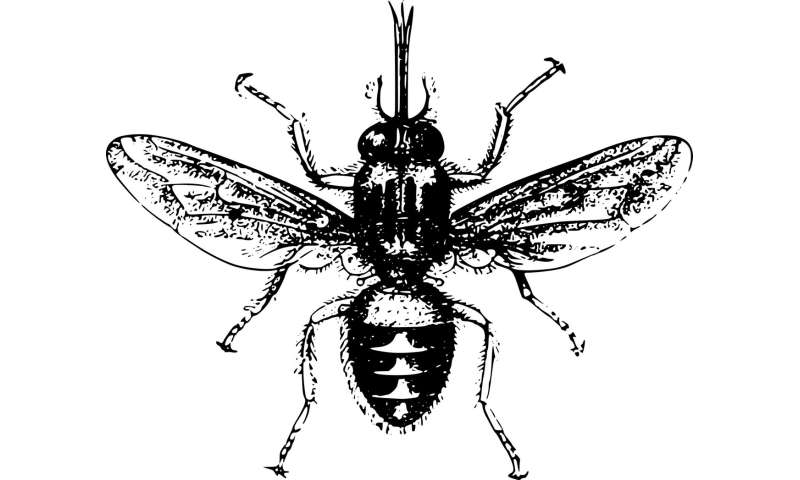

Over the past twenty years, huge efforts by a broad coalition of stakeholders, coordinated by the World Health Organization have curbed the latest epidemic of human African trypanosomiasis, a lethal disease transmitted by tsetse flies. Now, public health officials report in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases that the elimination of the disease as a public health problem is within reach, with fewer than 1,000 new cases reported in 2018.

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as sleeping sickness, is a parasitic infection that has wreaked havoc across Africa at different times in the 20th century. A slow-progressing form of the pathogen, Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, is found in western and central Africa, while a faster-progressing form, T. b. rhodesiense, occurs in eastern and southern Africa. Following a resurgence of the disease in the late 1990s, strengthened control and surveillance activities were put in place with the coordination of the World Health Organization. In 2012, the WHO’s Neglected Tropical Diseases roadmap targeted HAT for elimination as a public health problem by 2020.

In the new work, Jose Ramon Franco of the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland, and colleagues studied global indicators and milestones collected between 2017 and 2018 to monitor progress toward the 2020 goal of HAT elimination. The team also developed new country-level indicators to be used by endemic countries to track HAT and validate their elimination status.

977 cases of HAT were reported in 2018, down from 2,164 in 2016, and the area at moderate or high risk of HAT has shrunk to less than 200,000 square kilometers, the team reported. More than half of this area is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Eight countries meet the requirements to request validation of gambiense HAT elimination as a public health problem. In addition, health facilities providing diagnosis and treatment for gambiense HAT have increased since the last survey, while rhodesiense HAT facilities decreased in number.

Source: Read Full Article