Central Retinal Artery Occlusion a ‘Medical Emergency’

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is a medical emergency, and systems of care need to evolve to enable prompt recognition, triage, and management in a manner similar to that of cerebral ischemic stroke, the American Heart Association (AHA) concludes in a new scientific statement.

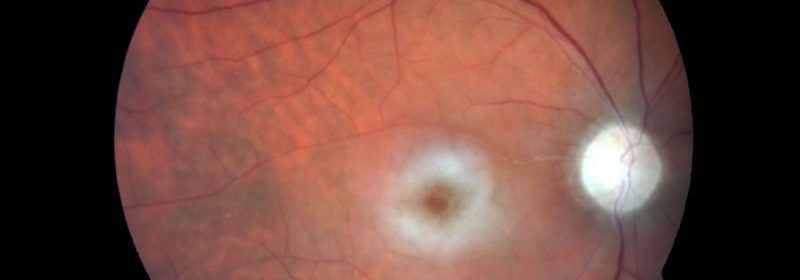

CRAO is a rare form of acute ischemic stroke that typically causes painless, immediate vision loss. Fewer than 20% of patients regain functional visual acuity in the affected eye.

CRAO is a harbinger of further cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events. It’s a “cardiovascular problem disguised as an eye problem,” Brian C. Mac Grory, MBBCh, who chaired the writing group, said in a news release.

Although much less common than stroke that affects the brain, CRAO is a “critical sign of ill health and requires immediate medical attention,” said Mac Grory, staff neurologist at the Duke Comprehensive Stroke Center, Durham, North Carolina.

“Unfortunately, a CRAO is a warning sign of other vascular issues, so ongoing follow-up is critical to prevent a future stroke or heart attack,” he added.

The 13-page AHA statement on management of CRAO was published online March 8 in Stroke.

The American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons Cerebrovascular Section has affirmed the educational benefit of the scientific statement, and it has been endorsed by the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society, the American Academy of Ophthalmology Quality of Care Secretariat, and the American Academy of Optometry.

No Evidence-Based Treatment

To assess the state of the science on CRAO, the writing group, with expertise in vascular neurology, neuro-ophthalmology, vitreo-retinal surgery, immunology, endovascular neurosurgery, and cardiology, conducted a comprehensive review of the world literature.

They report that the incidence of CRAO is about 1.9 per 100,000 person-years. The risk increases with age and in the presence of vascular risk factors, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, tobacco exposure, and obesity.

They say patients suspected of having CRAO should be triaged to the nearest emergency department, and they call for public outreach campaigns to emphasize that painless, monocular visual loss is a symptom of stroke.

CRAO and cerebral ischemic stroke share underlying mechanisms. In 95% of cases, CRAO occurs as a result of thromboembolic disease. In 5% of cases, it occurs as arteritic CRAO, usually as a component of giant cell arteritis.

Cerebral ischemic stroke and CRAO share therapeutic approaches. However, currently there are no widely accepted, evidence-based treatments for CRAO, and management of the condition varies, the writing group notes.

Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) may be considered for patients who have disabling visual deficits and who otherwise meet criteria for systemic tPA after a thorough benefit/risk discussion with the patient, the group advises.

“There is an unmet need for a pragmatic, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial comparing intravenous tPA with placebo at early time points in patients with CRAO,” they add.

In centers that can provide endovascular therapy, intra-arterial tPA may be considered for patients with disabling visual deficits at early time points, especially if they are not candidates for intravenous tPA.

“This consideration comes with the strong caveat that, at present, intra-arterial thrombolysis (IAT) is an unproven therapy and should be considered only in light of the devastating visual outcome associated with CRAO,” the writing group says.

Currently, there is no compelling evidence that conservative treatments for CRAO are effective. Trends in the observational literature suggest that ocular massage, anterior chamber paracentesis, and hemodilution may be harmful, the group says.

Hyperbaric oxygen is an emerging treatment that shows promise but requires further study.

Other potential treatments that require study include novel thrombolytics and neuroprotectants for use in tandem with other therapies to restore blood flow in the blocked artery.

The writing group says systems need to be developed to quickly recognize, triage, and manage patients with CRAO, akin to what happens now with cerebral ischemic stroke. The complexities of diagnosing and treating CRAOs require a team of specialists working together.

Secondary vascular prevention, including monitoring for complications, should be undertaken as a collaborative effort between neurologists, ophthalmologists, cardiologists, and primary care clinicians. Risk factor modification includes lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions.

Further studies are necessary to evaluate long-term quality of life after CRAO, and population-based studies are needed to more precisely clarify the modern epidemiology of CRAO.

The research had no commercial funding. Mac Grory has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The writing group included members of the AHA Stroke Council; the Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; the Council on Hypertension; and the Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease.

Stroke. Published online March 8, 2021. Abstract

For more from the heart.org | Medscape Cardiology, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Source: Read Full Article