Foot painters’ toes mapped like fingers in the brain

Using your feet like hands can cause organised ‘hand-like’ maps of the toes in the brain, never before documented in people, finds a new UCL-led study of two professional foot painters.

These findings, published in Cell Reports, demonstrate an extreme example of how the human body map can change in response to experience.

“For almost all people, each of our fingers is represented by its own little section of the brain, while there’s no distinction between brain areas for each of our toes,” said the study’s lead author, Ph.D. student Daan Wesselink (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and University of Oxford).

“But in other non-human primate species, who regularly use their toes for dextrous tasks like climbing, both the toes and fingers are specifically represented in their brains. Here, we’ve found that in people who use their toes similarly to how other people use their fingers, their toes were represented in their brains in a way never seen before in people.”

The two study participants are among three professional foot painters in the UK who paint holding paintbrushes between their toes. They also use their toes regularly for everyday tasks such as dressing themselves, using cutlery and typing. To do what most people would do with their two hands, both artists typically use one foot for highly dextrous tasks while using the other foot to stabilise.

Their distinctive experiences extend beyond behaviour; by not regularly wearing enclosed footwear, the foot painters get more complex touch experiences on their toes. This may also have impacted brain development of these organised toe maps.

For the study, funded by Wellcome and the Royal Society, the foot painters (as well as 21 people born with two hands, who served as a control group) completed a series of tasks testing their sensory perception and motor control of their toes.

The participants then underwent ultra high-resolution fMRI brain scanning of the brain’s body area—the somatosensory cortex. While inside the scanner, a researcher tapped the toes of the study participants, first looking for activity in the foot area of the body map.

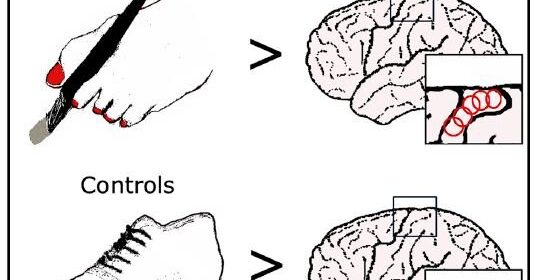

In the foot painters, specific sections of the brain’s foot area clearly reacted to their toes being touched. Brain maps comprised of individual toes were seen for the artists’ dextrous foot, with a similar but less pronounced pattern showing in their stabilising foot. The two-handed controls showed no such maps. Other analyses showed the foot painters’ feet were represented in the brain in a ‘hand-like’ way, but not the control participants’ feet.

The researchers also found that the foot painters’ toes were additionally represented in the part of their brain that would otherwise have served their missing hands. This corresponds with another study from the same lab finding that the brain’s hand area gets used to support body parts being used to compensate for disability, such as the lips, feet or arms of people who were born with only one hand.

Perhaps surprisingly, motor tasks showed the foot painters were not any better than controls at wiggling one toe at a time, but they did have heightened sensory perception for their toes compared to controls.

Peter Longstaff, one of the foot painters who took part in the study, said he was fascinated to learn about how his brain developed differently due to how he has used his feet. Longstaff, who ran his own pig farm for 20 years, turned to foot painting in 2002.

“I’ve enjoyed helping science by demonstrating how most people’s feet are not used to their full potential, and I hope the results will encourage other people to consider unconventional ways to get by without the use of hands,” he said.

The researchers say the findings reveal that all people may have an innate capacity for forming these ordered maps of each toe in the brain—similar to our monkey relatives. Most people’s brains don’t develop as such, however, probably due to a lack of necessary experience.

“The body maps we have in our brains are not necessarily fixed—it appears as such because they are very consistent across almost all people, but that’s just because most people behave very similarly,” said co-lead author Dr. Harriet Dempsey-Jones (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience).

“Our study demonstrates an extreme example of the brain’s natural plasticity, as it can organise itself differently in people with starkly different experiences from the very beginning of their lives,” said the study’s senior author, Dr. Tamar Makin (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience).

Source: Read Full Article