Understanding the spread of infectious diseases

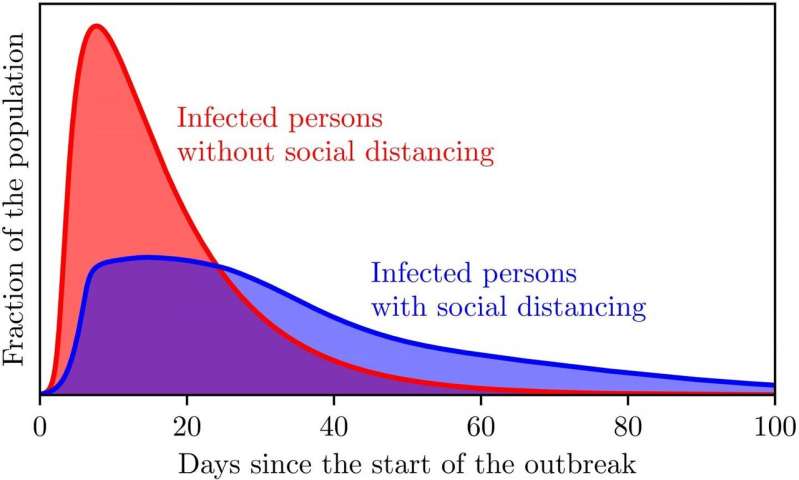

Scientists worldwide have been working feverishly on research into infectious diseases in the wake of the global outbreak of the COVID-19 disease, caused by the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. This concerns not only virologists, but also physicists, who are developing mathematical models to describe the spread of epidemics. Such models are important for testing the effects of various measures designed to contain the disease—such as face masks, closing public buildings and businesses, and the familiar one of social distancing. These models often serve as a basis for political decisions and underline the justification for any measures taken.

Physicists Michael te Vrugt, Jens Bickmann and Prof. Raphael Wittkowski from the Institute of Theoretical Physics and the Center for Soft Nanoscience at the University of Münster have developed a new model showing the spread of infectious diseases. The working group led by Raphael Wittkowski is studying Statistical Physics, i.e. the description of systems consisting of a large number of particles. In their work, the physicists also use dynamical density functional theory (DDFT), a method developed in the 1990s which enables interacting particles to be described.

At the beginning of the corona pandemic, they realized that the same method is useful for describing the spread of diseases. “In principle, people who observe social distancing can be modeled as particles which repel one another because they have, for example, the same electrical charge,” explains lead author Michael te Vrugt. “So perhaps theories describing particles which repel one another might be applicable to people keeping their distance from one another,” he adds.

Based on this idea, they developed the so-called SIR-DDFT model, which combines the SIR model (a well-known theory describing the spread of infectious diseases) with DDFT. The resulting theory describes people who can infect one another but who keep their distance. “The theory also makes it possible to describe hotspots with infected people, which improves our understanding of the dynamics of so-called super-spreader events earlier this year such as the carnival celebrations in Heinsberg or the après-ski in Ischgl,” adds co-author Jens Bickmann. The results of the study have been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Read Full Article