Precautionary Allergen Labels Often Misinterpreted

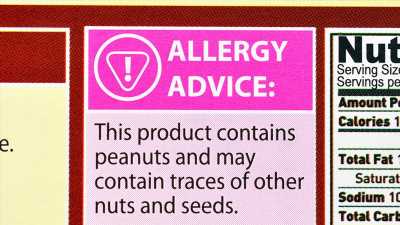

“May contain” statements and related warnings of possible allergens in food products often create confusion for consumers. In a recent study of adult consumers in the Netherlands, many consumers wrongly assumed that different wordings conveyed varying levels of allergen risk.

The study, which was published in the October issue of Clinical and Experimental Allergy, raises questions about the utility of precautionary allergen labeling and strengthens the call for clearer allergy information guidelines.

In accordance with the US Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act, food manufacturers are required to disclose on ingredient labels the presence of major allergens — milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybean. Legislation passed in April 2021 adds sesame to this list.

However, warnings about allergens that can slip into foods unintentionally during the manufacturing process are optional. Food allergies now affect up to 10% of people in Western countries. Although the use of precautionary labels has grown in parallel with rising concern about allergies, such labels are often unreliable. More than a third of food products that were identified in conjunction with accidental allergic reactions were found to contain undisclosed allergens, according to a 2018 study by Marty Blom, PhD, and colleagues. Blom is leader of the SRP Food Allergy Program at the Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research, in Utrecht, Belgium.

Labeling problems greatly complicate eating choices for patients with food allergies, many of whom “live in constant fear of an allergic reaction,” said André Knulst, MD, in an interview with Medscape Medical News. Knulst, a dermatologist and immunologist at the University Medical Center Utrecht, and Blom were co-authors of the new study, which was conducted by a multidisciplinary team led by linguistics professors at Utrecht University.

The researchers designed two online surveys to evaluate how consumers interpret allergen information. They recruited 238 participants who self-identified either as not having a food allergy or as having a food allergy or food intolerance. The first survey presented a series of fictitious foods in which the word “peanut” appeared either in the ingredients list, the warning label, or in neither. Study participants were asked whether they thought the product was unsafe for someone who is allergic to peanuts. In the second survey, participants were presented with warning labels that contained the phrase, “May contain peanut,” “May contain traces of peanut,” or “Produced in a factory which also processes peanut.”

On the whole, participants with food allergies took warning labels less seriously than participants who did not have food allergies. In addition, participants with allergies interpreted warnings differently in accordance with the phrasing on the lables. They perceived products labeled “produced in a factory” as less dangerous than those with warnings that contained the phrase “may contain” or “traces of.” “The same message is meant to be communicated — the product might be risky — but the patient thinks the different wordings mean different risks,” Knulst said.

Not surprisingly, participants assessed the risk as being higher when “peanut” was listed among the ingredients than when it appeared in the warning label. However, prior research has shown that products in which allergens are listed in the warning label can contain greater levels of the allergenic protein than products in which the allergen is listed as an ingredient, said co-author Leo Lentz, PhD, who studies document design and communication at the Utrecht Institute for Linguistics OTS.

Dr Steve Taylor

The reverse can also be true. Studies have shown that “you don’t find the allergen in 90% of the products that have the precautionary statement,” said Steve Taylor, PhD, professor emeritus in the Department of Food Science and Technology at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, in an interview with Medscape. Out of an abundance of caution, companies “put precautionary labels on all sorts of stuff that probably doesn’t need it,” Taylor said.

Dr Ruchi Gupta

Given the lack of regulation, many physicians encourage patients to avoid foods with warning labels regarding their allergens — despite the fact that this makes it hard for families whose members have food allergies to access affordable, nutritious, and safe foods, said Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, in Chicago, Illinois. In a study published in January in which her team surveyed 3004 food allergy stakeholders, more than half of the respondents considered current labeling practices a significant problem that interfered with their daily lives. “That is why working on a precautionary allergen label that is regulated and has clear thresholds listed is key,” Gupta said.

It’s a daunting task. Personal threshold doses can vary by five orders of magnitude. For some people, a speck of peanut dust can provoke a reaction, whereas others don’t experience a reaction until they eat half a dozen peanuts, Taylor said. “They’re both allergic, but one has to be a lot more careful.”

For more than a decade, researchers have combed publications and hospital records, meticulously collecting threshold data on thousands of allergic individuals. Warnings for unintended allergens should only be applied to products that exceed the reference dose; otherwise, the product should not have a precautionary label. In August, a group of experts from the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization issued a report in which they proposed establishing threshold doses below which no more than 5% of individuals with allergy would be predicted to experience a reaction to each major allergen. This is “a big step forward,” Blom said.

Gupta receives research support from the National Institutes of Health, Food Allergy Research and Education, the Melchiorre Family Foundation, the Sunshine Charitable Foundation, the Walder Foundation, the UnitedHealth Group, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Genentech. She serves as a medical consultant/advisor for Genentech, Novartis, and Food Allergy Research and Education. Taylor receives research funding from the Food Allergy Research and Resource Program and the US Department of Agriculture. He also receives royalties from Neogen Corp for reagents used in the development of food allergen residue detection methods.

Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:1374–1382. Full text

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article