Meet the vaccine appointment bots, and their foe

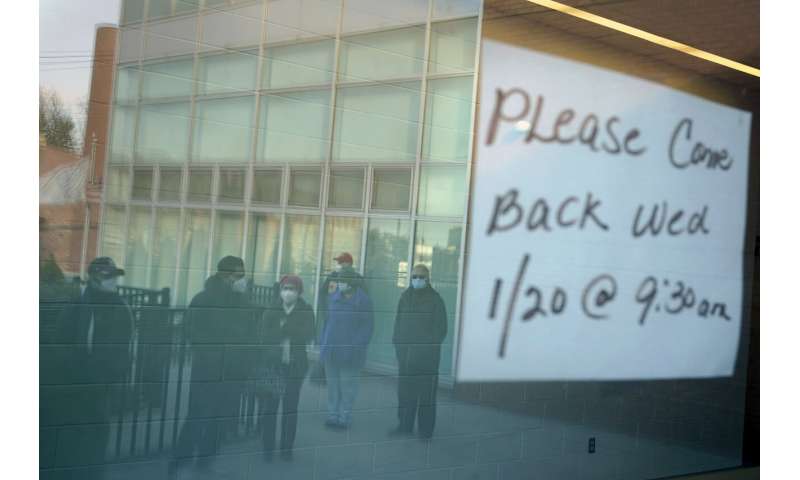

Having trouble scoring a COVID-19 vaccine appointment? You’re not alone. To cope, some people are turning to bots that scan overwhelmed websites and send alerts on social media when slots open up.

They’ve provided relief to families helping older relatives find scarce appointments. But not all public health officials think they’re a good idea.

In rural Buckland, Massachusetts, two hours west of Boston, a vaccine clinic canceled a day of appointments after learning that out-of-towners scooped up almost all of them in minutes thanks to a Twitter alert. In parts of New Jersey, health officials added steps to block bots, which they say favor the tech-savvy.

WHAT IS A VACCINE BOT?

Bots—basically autonomous programs on the web—have emerged amid widespread frustration with the online world of vaccine appointments.

Though the situations vary by state, people often have to check multiple provider sites for available appointments. Weeks after the rollout began, demand for vaccines continues to outweigh supply, complicating the search even for eligible people as they refresh appointment sites to score a slot. When a coveted opening does appear, many find it can vanish midway through the booking.

The most notable bots scan vaccine provider websites to detect changes, which could mean a clinic is adding new appointments. The bots are often overseen by humans, who then post alerts of the openings using Twitter or text notifications.

A second type that’s more worrisome to health officials are “scalper” bots that could automatically book appointments, potentially to offer them up for sale. So far, there’s little evidence scalper bots are taking appointments.

ARE VACCINE BOT ALERTS HELPING?

Yes, for the people who use them.

“THANK YOU! THANK YOU! THANK YOU! I GOT MY DAD AN APPOINTMENT! THANK YOU SO MUCH!” tweeted Benjamin Shover, of Stratford, New Jersey, after securing a March 3 appointment for his 70-year-old father with the help of an alert from Twitter account @nj_vaccine.

The success came a month after signing up for New Jersey’s state online vaccine registry.

“He’s not really tech-savvy,” Shover said of his father in an interview. “He’s also physically disabled, and has arthritis, so it’s tough for him to find an appointment online.”

The creator of the bot, software engineer Kenneth Hsu, said his original motivation was to help get an appointment for his own parents-in-law. Now he and other volunteers have set a broader mission of assisting others locked out of New Jersey’s confusing online appointment system.

“These are people who just want to know they’re on a list somewhere and they are going to be helped,” Hsu said. “We want everyone vaccinated. We want to see our grandparents.”

WHAT DO HEALTH OFFICIALS THINK?

The bots have met resistance in some communities. A bot that alerted Massachusetts residents to a clinic this week in sparsely populated Franklin County led many people from the Boston area to sign up for the slots. Local officials canceled all of the appointments, switched to a private system and spread the word through senior centers and town officials.

“Our goal was to help our residents get their vaccination,” said Tracy Rogers, emergency preparedness manager for the Franklin Regional Council of Governments. “But 95% of the appointments we had were from outside Franklin County.”

New Jersey’s Union County put a CAPTCHA prompt in its scheduling system to confirm visitors are human, blocking efforts “to game” it with a bot, said Sebastian D’Elia, a county spokesperson.

“When you post on Twitter, only a certain segment of society is going to see that,” he said. Even if they’re trying to help someone else, D’Elia said others do not have the luxury of people who are advocating for them.

But the person who created a bot that’s now blocked in Union County, 24-year-old computer programmer Noah Marcus, said the current system isn’t fair, either.

“The system was already favoring the tech-savvy and the person who can just sit in front of their computer all day, hitting refresh,” Marcus said.

D’Elia said the county is also scheduling appointments by phone to help those who might have trouble online.

HOW DO THEY WORK?

Marcus used the Python coding language to create a program that sifts through a vaccine clinic website, looking for certain keywords and tables that would indicate new appointments. Other bots use different techniques, depending on how the target website is built.

This kind of information gathering, known as web scraping, remains a source of rancor. Essentially, scraping is collecting information from a website that its owner doesn’t want collected, said Orin Kerr, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Some web services have taken web scrapers to court, saying scraping techniques violate the terms and conditions for accessing their sites. One case involving bots that scraped LinkedIn profiles is before the U.S. Supreme Court.

“There’s disagreement in the courts about the legality of web-scraping,” Kerr said. “It’s a murky area. It’s probably legal but it’s not something we have certainty about.”

WHAT ABOUT SCALPER BOTS?

The website for a mass vaccination site in Atlantic City, New Jersey says its online queue system—which keeps people waiting on the site as slots are allotted—is designed to prevent it from crashing and to stop bots from snapping up appointments “from real people.” But is that actually happening?

Making a bot that can actually book appointments—not just detect them—would be a lot harder. And sites usually ask for information such as a person’s date of birth to make sure they are eligible.

Pharmacy giants Walgreens and CVS, which are increasingly giving people shots across the U.S., have already said they’ve been working to prevent such activity.

Source: Read Full Article