Did Colorado’s COVID-19 exposure notification app succeed?

Fewer than 8% of people who tested positive for COVID-19 in Colorado since October used a state-promoted smartphone app to notify people they could have infected, but it may still have prevented additional cases.

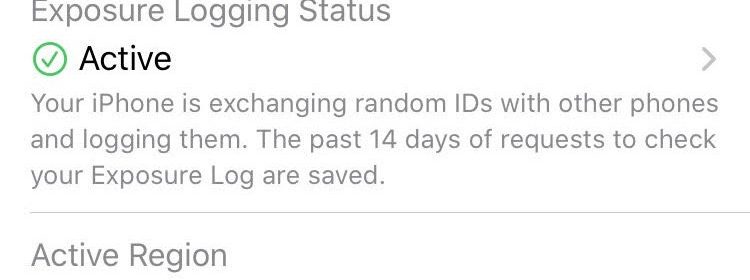

About 2.1 million people in Colorado have downloaded the app developed by Google and Apple, which exchanges tokens via Bluetooth with nearby phones that also have downloaded and activated it.

If a person tests positive for COVID-19, they receive a code they can use to send an anonymous notification to other people that person might have exposed. The app attempts to determine risk based on how close the person — or at least their phone — was to other people, how long they stayed nearby and how contagious the sender was, based on the day symptoms started.

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment reported it generated 377,007 codes for anyone who tested positive between October and mid-June, and 29,183 people used them to notify others whom they could have infected.

Some of the people who tested positive may not have had the app, while others might have chosen not to enter the notification code. A few Coloradans said they never got a code from the state, though it’s not clear if the problem was widespread.

At least 103,689 people received notifications that someone they had been close to during the time that person was possibly contagious had tested positive for COVID-19, but it’s not known how many others were exposed but not notified.

Many states used essentially the same app, with their health departments’ information subbed in. It was created by Google and Apple, and the two tech giants haven’t charged states to use it. It’s is available for free to Android users in the Google app store, and Apple users with recent-model iPhones received the option to use it as part of a software upgrade.

“We know that thousands of people have anonymously shared their positive diagnosis through the service, empowering other users they came in contact with to initiate testing and quarantine protocols as soon as possible,” the state health department said in a statement. “Colorado is proud to have been a pioneer in making use of this technology, and we believe the service will continue to support our COVID containment efforts as more and more Coloradans get vaccinated.”

It’s difficult to be certain how Coloradans’ use of the app compares. A study in Washington state found nearly 10% of codes were used to notify contacts, but most states haven’t published their data.

It’s even harder to know how well an app succeeded in preventing additional cases.

For it to work, a person who gets COVID-19 must have the app, get tested, receive a verification code and send it. Then, the people who could have been exposed must also have the app, and follow directions to quarantine — not something everyone can easily do, given that it could mean missing two weeks of work. And, of course, some people who show up as contacts weren’t actually infected, so notifying them doesn’t prevent new cases.

Colorado hasn’t attempted to quantify cases that were avoided, but studies in other places found wide possible ranges, depending on what they assume about how many contacts were infected and how well they followed quarantine rules. A study in the United Kingdom found the app could have prevented anywhere from 100,000 to 900,000 cases.

The U.K. study also found that the app notified roughly twice as many contacts as traditional tracing, perhaps because people forget who they saw recently, or didn’t exchange names with everyone. Use of the app was uneven, though, meaning people in some places were more likely to see a benefit than others.

It’s not shocking that people who had greater trust in public health were more likely to download the app, said Susan Landau, a professor of computer science at Tufts University’s School of Engineering. But since those who have the highest trust levels tend to be white and relatively well-off, the app may have been less effective for the essential workers who were at an increased risk of getting the virus.

When health departments do traditional contract tracing, they typically start by asking if the person can safely isolate at home, and if they need assistance getting food or other necessities, Landau said.

“It’s only after they do the caring kinds of things, do they move to, who could you have exposed,” she said.

Apps skip over that, so people may never know about supports that would help them safely isolate until they’re no longer contagious, Landau said. The biggest successes were those that paired an app with support for those in quarantine, she said.

An app “can be quite useful, but if you want it to work for the entire population, you need to support the ability to isolate,” she said.

Normally, use of apps and other new technology starts in a relatively small group of people, then spreads as more people see the advantages and want in, said Joanna Masel, an ecology and evolutionary biology researcher at the University of Arizona. That’s not practical for states that urgently need a tool during a pandemic, but smaller communities like universities have posted some of the best results, she said. About 25% of University of Arizona students who tested positive notified their contacts through an app.

Apps aren’t perfect, because they have to try to estimate when a person who recently tested positive became infectious, and can’t account for whether people were wearing masks, the ventilation in a space and whether they were engaged in riskier activities, like having a close conversation, Masel said. Still, studies suggest they do reduce the number of people the virus spreads to, she said.

“It’s not enough on its own. You have to have things like vaccines and masks,” she said. “It’s enough at the edges to make a difference.”

Source: Read Full Article