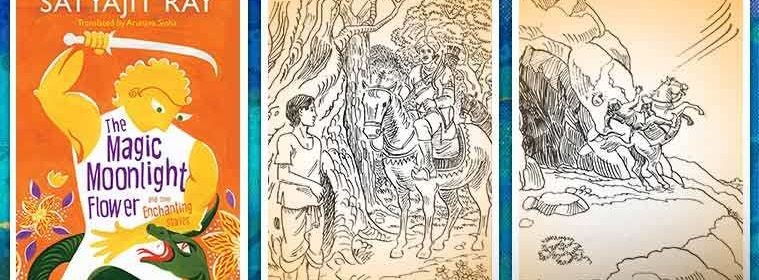

Satyajit Ray’s short story for kids: Sujan Harbola, the boy who spoke to birds

Cupping his hands around his mouth, Sujan leaned forward, took a deep breath, and emitted a roar. It was exactly like the roar of a tiger. And in a flash came a response from within the forest, ‘Roaaaarrrrr!’ The king was astounded.

By Satyajit Ray, translated by Arunava Sinha

There was a drumstick tree behind Sujan’s house. A robin lived in it. When Sujan was eight years old, he heard the robin’s call and thought, how beautifully this bird sings! Can human beings sing so well? From that day on, Sujan tried to imitate the call of the robin. One day, he suddenly discovered that the robin was returning his call. He realized that he had learnt the song of this particular bird. Even his mother Dayamoyee said, ‘How lovely, little one, I’ve never heard the cry of a bird in a human voice before!’ Sujan was very pleased.

Sujan was the son of Dibakar the grocer. He had an elder sister, who was already married. A brother had died at the age of three—Sujan had never even seen him. Sujan’s mother was very pretty, and he had inherited her nose and eyes. He had a clear complexion too.

Dibakar wanted his son to go to school, which was why he had Sujan admitted to Haran the schoolteacher’s pathshala. But Sujan was not remotely interested in studying. He sat in the small school with his palm-leaf notebook, listening to the cries of the birds from different trees and making up his mind to learn all of them. When the teacher asked Sujan to recite the five times table, he said, ‘Five oneza five, five twoza twelve, five threeza eighteen…’ The teacher boxed him on the ears and made him stand in a corner, from where he listened to the calls of the nightingale, the brain-fever bird and the cormorant and wondered how soon school would get over so that he could practise all these cries.

When Sujan had made no progress even after three years, Haran the schoolteacher went to Dibakar’s shop and told him, ‘Not even the gods will be able to give your son an education. My suggestion is that you withdraw him from school. It’s just bad luck—why else would your son have turned out this way? So many other boys are going to school and doing so well.’

Also Read: Satyajit Ray: Introduce your child to the maestro through these films and books

Dibakar had no choice but to call his son and ask, ‘What have you learnt at the pathshala in all this time?’

‘I’ve learnt the call of twenty-two different birds, Baba,’ Sujan told him. ‘There’s a banyan tree behind our pathshala and all sorts of birds are to be found in it.’

‘Do you want to be a mimic then—a harbola?’

‘A harbola? What’s that?’

‘Harbolas can imitate the sounds of different birds and animals. They make a living by performing their mimicry for audiences. Since you’ve made no headway with studies, you won’t be able to run the shop—you don’t even know how to add numbers. You’re of no use to me.’

So Sujan devoted himself to becoming a harbola. His favourite pastime was to wander about the fields and woods, listening closely to the cries of birds and beasts and imitating them. He never tired of this, for he was quite healthy and could walk long distances, climb trees and swim. When the birds responded to his cries by calling back, his heart danced in delight. All the birds seemed to be his friends. He had mastered the cries of cows and calves and sheep and goats too by listening to them closely in the fields. They too answered his cries when he imitated them. His mooing brought the old crone Nistarini out of her hut. Nistarini was under the impression that Dhabali’s calf had returned unexpectedly. Moti the washerman’s ass craned his neck and pricked up his ears, braying in response to Sujan’s brays, wondering where this other donkey had arrived from. Sujan could also mimic the neighing of the horse; he emitted this call outside the Haldars’, who were the zamindars, house. Hearing Sujan, Karim mian the groom asked himself, if that’s not my horse, whose horse is it?

As for birds, Sujan had mastered the calls of at least a hundred varieties. Crows and kites and sparrows and jackdaws and cuckoos and robins and pigeons and doves and parrots and mynahs and nightingales and tailor-birds and snipes and woodpeckers and barn owls—how many more to name? Sujan had perfected the calls of all these birds in the past few years. Like the humans of his village, the birds mistook his mimicry for the real thing, too.

How old was Sujan now? He wasn’t a child anymore. He could hardly be called khoka, or little boy, now. He was a young man, with a strong physique. His father said, ‘Time to get down to work. You’re old enough to earn a living now. Kartik the harbola lives in the next village. Tell him to help you. You could be his assistant for some time and then go your own way when older.’

Sujan went to meet Kartik, who was over forty and had been working as a harbola for twenty years. But Sujan discovered that Kartik didn’t know even half the cries that he did. Sujan had recently learnt to mimic the shehnai in a nasal tone, doing his own accompaniment on the tabla; he had also learnt to make the sound of a trumpet and of the anklets used by dancers. Kartik could not do any of this. He was astonished by Sujan’s skills but did not say anything out of envy. All he said was, ‘I don’t take apprentices. You’ll have to find your own way.’

‘If you could tell me how you got started, that would be of great help,’ said Sujan.

Kartik had no objection to this. ‘I performed as a harbola at the palace of Jantipur at the age of thirteen,’ he told Sujan. ‘The king was pleased and gave me a reward. That was when I became famous. If you can please a king, that’ll be a good start. I can’t help you.’

What could Sujan do? He didn’t know anyone, so how was he to perform at a royal palace? He went back home, dejected.

The name of Sujan’s village was Khira. There was a dense forest three miles north of Khira, on the other side of an enormous expanse of land. The name of the forest was Chanrali. No other forest was home to as many birds and animals as Chanrali was. One day, Sujan arrived in this forest while the sun was still up. He was not afraid of animals, nor, obviously, of birds. In the forest he mastered the calls of three unknown birds. When the sun began to go down to the west, Sujan heard the sound of hoofbeats, and then saw a herd of deer dashing away.

A little later he saw a king approaching on horseback through the forest, with six or seven followers, also on horseback. He was taken aback, for he had not expected to see other people in the forest. He realized that the king was out hunting.

On his part, the king was astonished to see Sujan too.

‘Who do you think you are?’ the king bellowed, stopping his horse.

Bowing, Sujan told the king his name.

‘Aren’t you afraid of tigers, roaming about alone in the forest?’

Sujan shook his head.

‘Does that mean there aren’t any tigers in this forest?’ asked the king. ‘I was told the Chanrali forest is full of tigers.’

‘Do you need tigers?’

‘Of course I do. Don’t you see I’m here on a hunt? What sort of hunt would it be without tigers?’

‘Haven’t you found any?’

‘We haven’t. We’ve found nothing except deer.’

‘I see.’

Sujan thought it over, and then said, ‘There is a tiger, and I can ensure you hear its roar, but will you kill this tiger, your majesty?’

‘Will I kill it? Of course! That’s what hunting is.’

‘But what harm has the tiger done you for you to kill it?’

The king was a good man at heart. Turning solemn, he said after a while, ‘Very well, I accept what you say. I shan’t kill the tiger, because it has indeed done no harm to me. But where’s the proof it exists?’

Cupping his hands around his mouth, Sujan leaned forward, took a deep breath, and emitted a roar. It was exactly like the roar of a tiger. And in a flash came a response from within the forest, ‘Roaaaarrrrr!’

The king was astounded.

‘You have a miraculous gift,’ he said. ‘Where do you live?’

‘The name of my village is Khira, your majesty. It is six miles away.’

‘Will you come to my kingdom with me? My kingdom is named Jabarnagar. It is sixty miles away. My daughter is to be married to the prince of Ajabpur next month. You will perform as a harbola at the wedding. Will you come?’

‘I have to inform my family, sir.’

‘Go home today, then. We’ve pitched our tents in the forest. We’ll spend the night here and go back in the morning. You must be here early tomorrow morning.’

‘All right.’

Sujan went back home and told his parents all that had happened. Dibakar was delighted. ‘The lord has smiled on us at last,’ he said. ‘You’ve got an opportunity.’

‘Won’t you come back?’ asked his mother.

‘Are you mad?’ said Sujan. ‘I’ll be back as soon as I’m done. And once I’m famous, I’ll go off on work from time to time, and come back from time to time.’

It was still dawn when Sujan left the next morning. By the time he reached the Chanrali forest, the sun had climbed a long way above the palm trees. A short search at the edge of the forest led him to the king of Jabarnagar’s camp in a clearing. The king was ready to go back home. ‘One of my men will take you on his horse, you’ll travel with him.’

Giving Sujan a chance to gorge on some delicious sweets and fruits first, the king left with his entourage for Jabarnagar. Sujan had never been on a horse before, though he had mastered the call of the horse. He rode in great joy, reaching Jabarnagar well before evening.

Sujan had never seen such a wonderful town, abounding in trees and houses and ponds and gardens and shops and markets. But he noticed something that surprised him greatly. He asked the king, ‘If there are so many trees and gardens here, why don’t I hear birds singing?’

Sighing, the king answered, ‘I can’t even begin to tell you how sad it makes me. Do you see that mountain there in the distance? Its name is Akashi. For five years now an ogre or demon or beast of some sort has been living there in a cave. He eats nothing but birds. I don’t know what magic he uses, but flocks of birds fly willingly into his cave, and the ogre just gobbles them up. There are no birds left in the city now, except a single popinjay in a cage in my daughter’s chambers in the palace.’

‘But how will the ogre survive if he runs out of food?’

‘Do you suppose my city is the only source of his food? There’s Ajabpur to the north of the mountain, Gopalgarh to the south—there’s no dearth of birds.’

‘Hasn’t anyone ever seen this beast?’

‘No, he doesn’t come out of the cave. I have personally waited outside the mouth of the cave with a bow and arrow. I had fifty armed soldiers with me. But he did not reveal himself. The cave is very deep. I went in part of the way with a torch, but saw no sign of him.’

Sujan had never heard of anything so strange. Could there actually be an ogre that ate nothing but birds? And how weird that it simply could not be defeated.

The king’s entourage had reached the palace by now. The king said, ‘You’ll stay in a room on the ground floor. Tomorrow morning you’ll perform your bird and animal sounds for my daughter. Her name is Srimati. There isn’t a girl in all of India as accomplished as she is. She has read the scriptures, grammar, history and mathematics; she knows the fairy tales and legends of every country, she even knows the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. She has been indoors all her life as I have never allowed her to be touched by sunlight. That’s why no one has a complexion as fair as hers.’

Sujan was confounded. A girl so learned? And here he was—a bundle of ignorance. He wouldn’t even be able to have a conversation with this princess.

‘Is this the princess who is to be married?’ he asked the king.

‘Yes, she’s the one. She will be married to the prince of Ajabpur, who is well-educated too. An excellent groom in terms of both looks and qualities.’

One of the king’s servants showed Sujan to his room at the palace. ‘You can rest today,’ said the king. ‘They’ll bring you to me tomorrow. Then we’ll test your skills.’

‘Just a minute, your majesty.’ Sujan simply could not help but bring up the subject of the bird-eating ogre.

‘What is it?’

‘How far is the Akashi mountain?’

‘Eight miles. Why?’

‘Just asking.’

When Sujan saw his room, he knew the king was pleased with him. It was a nice large room with a bed with beautiful patterns besides other furniture of wood and ivory. Sujan had never even seen, leave alone used, an eiderdown pillow as soft as the one on the bed.

The food that was served to him at night was also of a kind he had never tasted. There were so many courses, and how delicious, how aromatic. The sweets alone were of five different kinds. How could he possibly eat so much?

Express Opinion

When he had eaten his fill, Sujan began to ponder. He kept thinking of the ogre over and over again. Birds were such lovely creatures—how could the ogre have the heart to gobble them up? His appetite was so vast that he had eaten up all the birds in the city! How about visiting his den? Sujan was not sleepy yet. There was a full moon in the sky. He already knew which way the mountain lay, it was just a matter of finding the cave.

Sujan got out of bed, muttered a prayer and went out. Since everyone knew him by now, no one asked any question.

Under the bright moonlight Sujan set off directly for the base of the mountain. There wasn’t a soul anywhere, even the night owls had probably been consumed by the ogre.

As Sujan walked around the base of the mountain and reached its northern face, he saw a dark cave thirty or forty yards up the mountainside.

This must be the ogre’s cave. Did it eat humans too? Sujan hoped not.

Gathering courage, he began to climb.

Here it was, the mouth of the cave. Since the moon was on the other side of the mountain, it was impenetrably dark inside the cave.

An unusual sort of courage had grown out of the rage in Sujan’s heart. Birds were his friends, and they were being eaten by the ogre; hence his rage.

Sujan entered the dark cave.

But barely had he taken ten steps when he had to retrace those same ten steps as quickly as an arrow.

He had heard a horrible roar. No beast could emit such a dreadful cry.

This was an ogre, and the ogre had seen Sujan, and it hadn’t liked what it had seen.

After this incident, Sujan lost no time returning to his room in the palace. The next morning, one of the palace employees took him to meet the king. He was not in his court yet. He would make his daughter hear the cries of birds and beasts as performed by Sujan before attending to matters of state. Sujan realized how strong a bond the king had with his daughter.

Princess Srimati had already heard of Sujan the previous night—how he had imitated the roar of the tiger to prove that the beast did indeed live in the forest. She had not heard the call of any animal in her life except that of a cat’s. Even when there were birds in the city five years ago, she had not heard any of them sing, besides her popinjay. How could she, for she never left her room. She was not to be touched by sunlight. She had not seen the sun, never seen nature with her own eyes. True, she had learnt a great deal from books, but how much can books teach you? Reading books is not the same as seeing with your own eyes or hearing with your own ears, is it? Srimati knew the names of every bird in Bengal, but she had never heard their calls or their songs for herself.

When Sujan reached the yard of the inner chambers, Srimati had left her own room for another one. This room had an open window, so that any music played in the yard could be heard here. Sujan was to perform his feats as a harbola in the yard.

As soon as the clock struck eight, the king told Sujan, ‘Well, what are you waiting for? My daughter’s sitting up there, she can hear you.’

Since it was spring, Sujan began with the calls of the cuckoo and the robin. No one had ever heard a human voice capable of creating such amazingly lifelike bird sounds. Jabarnagar heard birdsong for the first time in five years.

The princess had tears in her eyes right away. Softly, she said, ‘Oh, how lovely! Is this how birds sing? And has the ogre eaten up all the birds? It’s so unfair, so unfair!’

Sujan produced one bird call after another. The king’s chest swelled with pride, and the princess’s heart began to flutter. Couldn’t she at least get a glimpse of this person with such skills?

There was a veranda outside the room, covered with beautiful fabric. Parting it in one corner afforded a view of the courtyard below. The princess’s best friend was seated by her side. Srimati needed to get rid of her. ‘I’m thirsty, Suradhuni, can you get me a glass of water please?’ said Srimati.

Her friend would have to go all the way to the bedroom to fetch the water, which would give her some time.

Suradhuni left.

Srimati raced out to the balcony, parted the fabric and peeped out at the young man below. He was mimicking the cry of the common iora now. Srimati quite liked him; but she realized from his clothes that he was poor.

She was back at her place in the room before Suradhuni could be back with a glass of water.

Sujan performed for an hour. No one in the Jabarnagar palace had ever heard or seen such a show. As for the princess, she had never even heard these cries. A new world had opened up to her—the world of nature, which she had not known in all her sixteen years. This young man from a poor family had brought new joy into her life.

As she reflected on all this, Srimati recollected that she was getting married next month. Her betrothed, Prince Ranabir, had promised that arrangements would be made for her to continue her education. There would even be a room for her in the inner chambers, shielded from the sun. What if the sunlight darkened the princess’s complexion?

Sujan didn’t see the princess, however. The king had shown him a hand-drawn portrait, saying, ‘Here, this is what my daughter looks like.’ The portrait looked like a nymph from heaven. When he heard that the princess had been charmed by his performance, he was very proud of himself. Besides, the king had rewarded him handsomely, too. He gave a diamond ring and one hundred gold coins. Sujan knew that this money would be enough for his family to live their entire lives in comfort.

Just one thought twisted his heart. If only he could overcome the ogre.

A month passed in no time. In this period Sujan had been to nearby towns quite a few times, performing his harbola calls and earning some more money, most of which he had turned over to his father. It was evident to him that his fame was beginning to spread. He spent much of his time at the royal palace practising new calls. How could he forget that he would have to perform at the coming wedding, where he would have to uphold the reputation of the king of Jabarnagar.

Although elaborate arrangements were being made for the wedding, no one knew the state of mind that Srimati was in. Her heart was as hidden away as her life. But it was true that no one had seen her smile in the past one month. Sujan practised bird calls in his room on the ground floor, the faint sounds of which floated into the inner chamber on the first floor. Srimati’s heart lurched at these distant sounds. The young man was so talented! She wondered what it would be like to talk to him.

Her curiosity had peaked in this one month. He could mimic such extraordinary calls, he was so handsome and yet simple…Srimati simply had to find out what sort of person he was. She blurted this out to Suradhuni one day.

Suradhuni had been Srimati’s friend and confidante for five years. She did not approve of Srimati being kept locked away in a room. She gave Srimati descriptions of what the trees and rivers and roads and fields looked like in the bright light of morning. She also told Srimati that she had once seen real birds.

‘You have to do something for me,’ Srimati told her.

‘What?’

‘You have to find out how to get to the harbola’s room.’

Suradhuni promised to find out.

She went out of the inner chambers and bribed a guard with a gold coin she had taken from Srimati. The guard told her where Sujan’s room was. At the time, Sujan was practising the song of the coppersmith.

As he was about to go to bed that night after his meal, Suradhuni entered his room.

‘What’s all this!’ exclaimed Sujan.18

Putting her finger on her lips, Suradhuni signalled for Srimati to enter.

‘You!’ Sujan said in surprise. ‘I’ve seen your portrait.’

‘I came to talk to you,’ Srimati said calmly. ‘You have opened up a new world for me.’

‘But what will I talk to you about? I am not educated. I can’t even recite the five times table, and I’ve heard you’ve studied a lot. So…’

‘Have you seen the sun?’

‘Yes, I see it every day. When the sun rises it makes the sky so red it seems as if it has smeared vermilion on the sky. This happens also when it sets. The birds start singing even before sunrise. They go back to their nests as soon as the sun sets.’

‘Have you seen flowers in spring?’

‘Yes. I see them even now. Every day. Red and blue and yellow and white and purple—so many different colours. The bees sip the honey, the butterflies hover around the flowers. Buds blossom. The flower blooms and then falls to earth. The leaves turn a tender green in spring, in winter they dry up and drift to the ground.’

‘There’s something that makes me very sad.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Birds sing so beautifully but they’ve all been eaten up by that ogre. I won’t be happy till he’s punished.’

‘But your wedding’s coming up. How can you be unhappy now? Weddings are such fun.’

‘I used to think so too, but I’m not happy anymore ever since I heard the song of birds from you. I’ve told my father.’

‘What have you told him?’

‘I will marry the man with whom my wedding has been fixed only if he kills the ogre. That’s my condition for marrying him.’

‘What if someone else kills him instead?’

‘I will marry whoever kills him. Anyone who isn’t strong enough to do this is not a man at all.’

‘It’s a very difficult condition.’

‘Why do you say that?’

‘I’ve been to the ogre’s cave. I ran away at his roar. It was horrible.’

‘I’m very sorry to hear that. You’ve been mimicking the calls of tigers and lions, I thought you were courageous. Anyway, I will only marry the person who can kill this avesvore.’

‘Is he called an avesvore?’

‘Yes.’

‘How did you know?’

‘I’ve read it in a book. Aves means birds.’

The conversation ended there. Srimati returned to her room with Suradhuni.

Sujan had to go to Markatpur the next day. Pleased with his performance, the king of Markatpur gave Sujan a fat reward. Sujan returned to Jabarnagar. Following Srimati’s orders, he had to perform all the birds’ cries for her once a day, and the king gave him a reward every day too.

The king was deeply worried. His daughter had resolved not to marry anyone but the person who slayed the ogre. So Prince Ranabir of Ajabpur was visiting Jabarnagar the next day. He would have to go to the cave in Akashi mountain alone. Only if he was successful would he be able to marry Srimati. Ranabir was renowned as a bold warrior so the king of Jabarnagar was confident that he would pass this test.

Meanwhile Sujan was thinking to himself I’ll never forget the roar I heard. If that was the ogre’s cry, who knows what he must look like, and how powerful he must be. Will the prince of Ajabpur really be able to kill this ogre?

The prince arrived on horseback shortly after sunrise the next day. He was dressed in armour, with a sword at his waist, a quiver of arrows slung at his back, and a bow in his hand. In addition, a spear was tucked into a holster on the horse’s flank.

The prince was accompanied by two other horsemen who had brought three vultures from the cremation ground in a net. The 21 vultures would be tossed into the mouth of the cave to entice the ogre out of his den—that was their plan.

A large number of Jabarnagar’s citizens had gathered on the plain opposite the cave to watch the battle. Although the king of Jabarnagar was not present in person, he had sent a messenger to find out the outcome.

Prince Ranabir was prepared now. His companions threw the vultures, still in their nets, on the ground outside the cave, blowing on their horns to announce their presence. Then they moved aside, leaving Ranabir to approach the cave on horseback.

One of the onlookers was more interested than all the rest—Sujan. Having heard of the impending battle, he had arrived in front of the cave before everyone else. He did not know why, but in his heart he kept hoping that the prince would not be successful.

But what was this? Why wasn’t the ogre coming out? Why was he still inside the cave despite such a delicious bait?

Meanwhile, the prince’s horse had started fidgeting restlessly. Now the prince gathered courage and advanced towards the cave. He also blew on his horn twice or thrice. The very next moment everyone’s blood ran cold. There was a violent roar, which made the prince’s horse rear backwards with its front legs in the air, depositing its rider on the ground, and galloping off in the opposite direction. The prince was forced to run behind it. It was obvious that he had accepted defeat to the ogre. He was not valiant enough to enter into battle against someone with a roar like that.

Those who had crowded around the cave also ran away helter-skelter. Only one among them, Sujan, thought about something gravely for a few minutes before returning with measured footsteps.

After Ranabir, the princes of seven other kingdoms tried to kill the avesvore, only to run for their lives when they heard him roar. Along with this, the princess’s wedding kept being postponed, and the wrinkles of worry on the king’s forehead kept deepening.

Sujan had been on the spot to see the pathetic condition of the eight princes; he had observed for himself that the demon’s roar had generated terror not just in the horses but also in their riders.

Thanks to these eight people accepting defeat, none of the other princes in the land dared to attempt slaying the monster of Jabarnagar.

On the ninth day, as soon as the king emerged from the temple after completing his prayers, he found Sujan waiting for an audience. The king was miserable. He asked grimly, ‘What is it Sujan, what do you need now?’

‘Can you give me a spear, your majesty?’ asked Sujan.

‘What will you do with a spear?’ the king said in surprise.

‘I will try to kill the avesvore.’

‘Are you out of your mind?’

‘Let me try, your majesty. Since he is a creature, he is alive, and if he is alive, his heart is beating. If I can spear his heart, he’s bound to die.’

‘But he doesn’t even come out of this cave.’

‘What if he does today? No one knows what’s on his mind, after all.’

The king pondered briefly, his eyes on Sujan. ‘Very well,’ he said, ‘we don’t lack for spears. I’ll make arrangements. You look like someone who won’t give up till he’s done what he wants to.’

Sujan got his spear shortly. Taking a horse from the stable, he set off on horseback for Akashi, holding the spear.

The king had developed a soft spot for Sujan; he too quickly mounted a horse and followed Sujan towards the mountain to learn of the boy’s fate.

Sujan let the horse go before reaching the mouth of the cave. He knew that if the horse were to bolt out of fear, he would have to run away as well.

The inside of the cave was as black as night, because it faced the north.

Meanwhile, the king had also arrived at the spot. He decided to watch the proceedings on horseback, from a distance. There was no crowd today, for an announcement had been made in the city that there would be no more attempts to slay the ogre.

Sujan approached the cave on tiptoes, holding the spear. There was silence everywhere. This was because there were no birds, for birds cannot but sing in the morning.

Muttering a prayer, and with a glance at the sun, Sujan drew in a lungful of air and, as he exhaled, emitted the horrible roar that he had practised over the past nine days. The king’s horse reared up in fear at the cry, but his master managed to quieten him.

Then came the response to the roar—and it was impossible to tell whether the creature that leapt out of the cave into the sunlight was a human or an ogre or a beast. It could be said to be a grotesque combination of all three, the sight of which would make people drop dead with fear.

But Sujan the harbola only had eyes for the spot on the creature’s body where the heart should be. Aiming for this spot, he threw the spear with all his might.

He didn’t remember anything after this.

When Sujan came to, the first thing he saw was the face in the portrait that had made his heart dance with joy.

The king stood next to Srimati. ‘The ogre is dead,’ he said, ‘so I am giving my daughter to you. The wedding shall take place seven days from now. Word will be sent to your parents in the village of Khira. They will live here after the wedding, as will you.’

‘And my education?’

‘That’s my responsibility,’ said Srimati with a smile. ‘We’ll start with the five times table—on the wedding day. And until birds return to the kingdom, you will mimic their song for me.’

‘May I say something in that case?’

‘Do.’

‘Don’t keep yourself imprisoned in a room anymore.’

‘No, never again.’

‘And set your popinjay free. Birds shouldn’t be kept in cages. They’re miserable when they cannot fly.’

‘All right,’ nodded Srimati.

(Excerpted with permission from The Magic Moonlight Flower and Other Enchanting Stories by Satyajit Ray, translated by Arunava Sinha, published by Red Turtle, an imprint of Rupa.)

Source: Read Full Article