Yearly Lung Cancer Scans Are Advised for People 50 and Over With Shorter Smoking Histories

New guidelines from medical experts will nearly double the number of people in the United States who are advised to have yearly CT scans to screen for lung cancer, and will include many more African-Americans and women than in the past.

The disease is the leading cause of U.S. cancer deaths, and the goal of the expanded screening is to find it early enough to cure it in more people at high risk because of smoking. In those individuals, annual CT scans can reduce the risk of death from the cancer by 20 to 25 percent, large studies have found.

The new recommendations, by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, include people ages 50 to 80 who have smoked at least a pack a day for 20 years or more, and who still smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.

The advice, published on Tuesday in the medical journal JAMA, differs in two major ways from the task force’s previous guidelines, issued in 2013: It lowers the age when screening should start, to 50 from 55, and it reduces the smoking history to 20 years, from 30.

Those changes will add more women and African-Americans to the pool eligible for screening, because they tend to smoke less heavily than the white male study participants on whom earlier guidelines were based. Women and Black Americans also tend to develop lung cancer earlier and from less tobacco exposure than do white men, experts said.

Why the risk appears to differ by race and gender is not known.

“Some studies have alluded to some hormonal influences in women,” Dr. Mara Antonoff, a lung surgeon at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said in an interview. “In terms of racial differences, we don’t have an answer. We have population-based data to show they have a tendency to develop lung cancer younger and with less exposure to tobacco, but we don’t have a mechanism.”

Under the new criteria, 14.5 million people in the United States will qualify for the screening, an increase of 6.4 million.

The task force includes 16 physicians, scientists and public health experts who periodically evaluate screening tests and preventive treatments. Members are appointed by the director of the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, but the group is independent and its recommendations often help shape U.S. medical practice.

The use of chest X-rays to detect lung cancer was largely abandoned decades ago because they could not find the disease early enough to be useful.

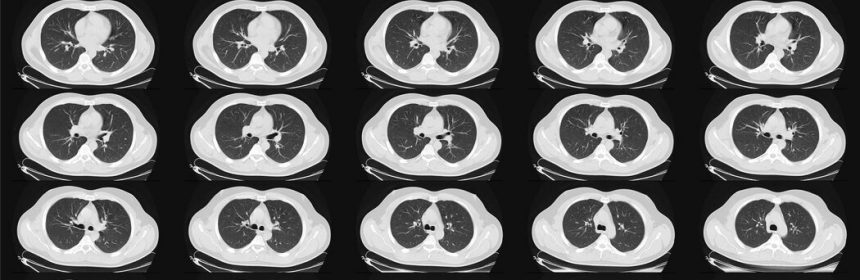

The CT scans, called low-dose CT — because they involve a relatively small amount of radiation — cost about $300. Patients are advised to stop the screening once they have not smoked for 15 years, or if they develop health problems that would substantially shorten their life expectancy or make them unable to have lung surgery if needed.

Patients have not flocked to clinics for this screening. Researchers estimate that only 6 to 18 percent of those who qualify and could be helped by the screening have taken advantage of it. Some cannot afford it.

“Part of the low uptake is simply lack of access to care,” said Dr. Robert Smith, a screening expert at the American Cancer Society. “Smoking in general is increasingly concentrated in lower-income populations.”

The Affordable Care Act does require that insurers cover any screening broadly recommended by the task force, with no out-of-pocket costs.

But researchers have found that half the population eligible for lung-cancer screening had either no insurance, or Medicaid, Dr. Smith said. Not all Medicaid plans have covered the screening, according to an editorial in JAMA.

“There could be a 15-year period when you might quality for screening and not have any insurance,” Dr. Smith said.

He and other researchers also said that patients may be missing out on lung-cancer screening because they just don’t know about it. It has not received as much attention as other cancer screenings, like mammograms, colonoscopies and Pap tests. Some doctors may not encourage it as strongly, and especially with former smokers, may not take the time to calculate a patient’s smoking history to see if it matches the guidelines.

The changes in the criteria for smoking history and screening age were based on new data from multiple studies, Dr. Alex H. Krist, the task force chairman and a professor of family medicine and population health at Virginia Commonwealth University, said in an interview.

“Lung cancer is the No. 1 cancer killer in America,” Dr. Krist said, adding that with the new data, “we have even more confidence that screening does save lives.”

Like other kinds of screenings affected by the pandemic, those for lung cancer remain below 2019 levels, according to an analysis of Medicare data by Avalere Health, a consulting firm, conducted for Community Oncology Alliance, which represents independent cancer specialists.

While the number of screenings had started to rebound in the summer, the fresh spike in Covid cases later in the year caused them to fall again. In November, screenings were down by 30 percent, compared to 2019, and the number of lung biopsies had also dropped, indicating cases were not being diagnosed.

Using its own grading system, the task force gave its recommendation a B, saying there was “moderate certainty” that annual screening was of “moderate net benefit.”

That may not sound like a ringing endorsement, given that a grade of A means “high certainty that the net benefit is substantial.” But anything with an A or B grade should be offered to patients, according to task force rules.

“There is building evidence that a pretty simple, five-minute, low-dose, low radiation scan can really save a lot of people’s lives,” said Dr. Bernard J. Park, a lung surgeon and the clinical director of the lung-screening service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. About 75 to 85 percent of the cancers found with this screening are Stage 1, and curable with just surgery or radiation, he estimated.

Dr. Park said that many people who signed up for the screening had quit smoking or were trying to stop, but that a few regarded clear scans as a sign that they could keep smoking.

Dr. Smith said that the American Cancer Society was due to revise its own guidelines for lung-cancer screening, and that its advice would probably be similar to that of the task force.

In 2013, the American Academy of Family Physicians declined to recommend for or against CT screening for lung cancer, saying there was insufficient evidence. But the president, Dr. Ada Stewart, said in an emailed statement on Monday that the academy would review the new task force evidence and decide whether to update its own recommendation to its members.

Globally, there were 2.09 million new cases of lung cancer in 2018, and the disease is also the leading cause of cancer deaths, killing 1.76 million people that year, according to the World Health Organization.

There were 228,820 new cases of lung cancer in the United States in 2020, and 135,720 people died from it, according to the National Cancer Institute. About 90 percent of cases occur in people who smoke, and current smokers’ risk of developing the disease is about 20 times that of nonsmokers.

Only about 20.5 percent of patients survive five years after the diagnosis. Most cases are diagnosed late, after the cancer has begun to spread. But if it can be found and treated early, cure is possible, doctors say.

CT screening has risks, and doctors say those must be explained to patients, who may decide to decline the testing. The scans detect tiny nodules in the lungs that may be early cancers — or maybe not. A suspicious-looking spot could be just a minor infection, inflammation or a benign growth, Dr. Park said.

Often, the nodules can just be monitored with repeat scans, but it can be nerve-racking for patients to spend months waiting for the next test, knowing there is something in their lung that might be malignant.

False positive rates, when something harmless is mistaken for cancer, have ranged from 3.9 to 25 percent and higher in studies, but tend to decrease over time, as the patient has more annual scans.

A major concern about false positives is that they can lead to invasive procedures like lung biopsies. One large study found that invasive procedures were performed needlessly in 1.7 percent of the patients who were screened. The task force report said that standards created by radiology societies for evaluating the scans could help to prevent some unnecessary procedures spurred by false positives.

Another possible risk from screening is the chance that the cumulative radiation exposure could cause cancer. But the dose is low, and the risk is thought to be small, especially when compared with the risk of lung cancer caused by smoking.

In theory, screening could also lead to unneeded invasive tests and treatment for a cancer that would not have progressed or harmed the patient. How often that might occur is not known, but it is considered rare.

Reed Abelson contributed to this article.

Source: Read Full Article