The Diagnosis Is Alzheimer’s. But That’s Probably Not the Only Problem.

Allan Gallup, a retired lawyer and businessman, grew increasingly forgetful in his last few years. Eventually, he could no longer remember how to use a computer or the television. Although he needed a catheter, he kept forgetting and pulling it out.

It was Alzheimer’s disease, the doctors said. So after Mr. Gallup died in 2017 at age 87, his brain was sent to Washington University in St. Louis to be examined as part of a national study of the disease.

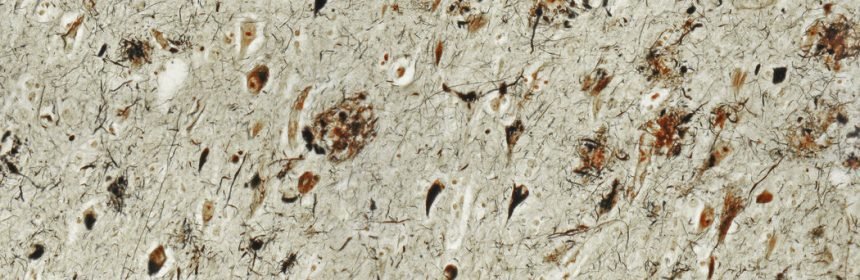

But it wasn’t just Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers found. Although Mr. Gallup’s brain had all the hallmarks — plaques made of one abnormal protein and tangled strings of another — the tissue also contained clumps of proteins called Lewy bodies, as well as signs of silent strokes. Each of these, too, is a cause of dementia.

Mr. Gallup’s brain was typical for an elderly patient with dementia. Although almost all of these patients are given a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, nearly every one of them has a mixture of brain abnormalities.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

For researchers trying to find treatments, these so-called mixed pathologies have become a huge scientific problem. Researchers can’t tell which of these conditions is the culprit in memory loss in a particular patient, or whether all of them together are to blame.

Another real possibility, noted Roderick A. Corriveau, who directs dementia research programs at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, is that these abnormalities are themselves the effects of a yet-to-be-discovered cause of dementia.

These questions strike at the very definition of Alzheimer’s disease. And if you can’t define the condition, how can you find a treatment?

In addition to plaques and tangles, other potential villains found in the brains of people with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s include silent strokes and other blood vessel diseases, as well as a poorly understood condition called hippocampal sclerosis.

Potential culprits also include an accumulation of Alpha-synuclein, the abnormal protein that makes up Lewy bodies. And some patients have yet another abnormal protein in their brains, TDP-43.

No one knows how to begin approaching the multitude of other potential problems found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. So, until recently, they were mostly ignored.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a dirty little secret,” said Dr. John Hardy, an Alzheimer’s researcher at University College London. “Everybody knows about it. But we don’t know what to do about it.”

In interviews, some experts said they had been reluctant to talk much about mixed pathologies for fear of sounding too negative. But “at a certain point we have to be somewhat more realistic and rethink what we are doing,” said Dr. Albert Hofman, chairman of the epidemiology department at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The problem began with the very discovery of Alzheimer’s disease. In 1906, Dr. Alois Alzheimer, a German psychiatrist and neuroanatomist, described a 50-year-old woman with dementia.

On autopsy, he found peculiar plaques and twisted, spaghetti-like proteins known as tangles in her brain. Ever since, they have been considered the defining features of Alzheimer’s disease.

But scientists now believe this woman must have had a very rare genetic mutation that guarantees a person will get a pure form of Alzheimer’s by middle age.

Patients with the mutation appeared to develop only plaques and tangles, and no other pathologies. So for decades, plaques and tangles were the focus of research into dementia.

The rare genetic mutations led to an overproduction of amyloid, it turned out, the abnormal protein in those plaques. To many scientists, that suggested that amyloid was the fundamental cause of Alzheimer’s disease.

More plaques usually meant more severe dementia, in both older and younger patients. So researchers tested drugs that could attack amyloid or stop its production in genetically engineered mice. The drugs worked beautifully.

Scientists recognized that mice were an imperfect model — they never develop dementia — but the studies were encouraging. So it was a huge disappointment when, over and over, those drugs failed in clinical trials in patients.

Tests of anti-plaque drugs continue, despite the increasing recognition that many factors may combine to cause dementia — or that, perhaps, the true cause has yet to be found.

“What motivates us is the depth of the unmet need,” said Dr. Dan Skovronsky, chief scientific officer of the drug company Eli Lilly, which continues to investigate anti-amyloid treatments.

“That’s why we keep going forward. But it is such a tough, tough problem, and made tougher because of the mixed pathology.”

What to do now? Scientists are struggling the reframe the problem. Some think research should be more focused on age.

“We can’t avoid the fact the number one risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is age, and many of these other pathologies are age-associated,” said Dr. John Morris, a professor of neurology at Washington University in St. Louis. “We don’t see them in younger people.”

Carol Brayne, an epidemiologist at Cambridge University, has been saying as much for decades. There is something significant, she has found, about the obvious fact that the older a person gets, the more likely he or she is to develop dementia. By their 90s, one out of every two people has dementia.

A more optimistic view is that there may be something in the brain that sets off a cascade of multiple pathologies. If true, blocking that factor could stop the process and prevent dementia.

Dr. Hofman is convinced that the precipitating factor is diminished blood flow to the brain. “Alzheimer’s disease is a vascular disease,” he said.

Supporting this view, he added, are data from nine studies in the United States and Western Europe consistently finding a 15 percent decline in the incidence of new Alzheimer’s cases over the past 25 years.

“Why is that? I think the only reasonable candidate is improved vascular health,” Dr. Hofman said. The most important factor is the decline in smoking, he believes, but people in rich countries also are more likely to better control high blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

Dr. Seth Love, professor of pathology at the University of Bristol in England, noted that a core feature of Alzheimer’s is a reduction in blood flow through the cerebrum of the brain.

That happens even in people with the genetic mutation that leads Alzheimer’s in middle age. Fifteen to 20 years before these people have dementia, blood to their brains slows.

“We don’t know why,” Dr. Love said.

Or perhaps it really is amyloid that begins the avalanche of other problems.

Some researchers still hold out hope that if anti-amyloid drugs are started early enough, they might prevent dementia. Clinical trials are testing the idea now in people genetically disposed to get Alzheimer’s disease.

But even if the drugs work, will they work in the elderly patients who make up the bulk of those with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis — but who don’t have anything resembling a pure form of the disease?

Perhaps those drugs will have only a small effect in patients with mixed pathologies, Dr. Hardy said. It would take gigantic trials going on for years to see such a tiny effect.

“Those aren’t the kind of medicines we are looking for,” said Dr. Skovronsky, of Eli Lilly. “We want something that has a big effect.”

Dr. Skovronsky has been forced to do some soul-searching. Trying anti-amyloid drugs in old people in the early or middle stages of Alzheimer’s just is not working.

But when is it best to intervene, and in whom? And do scientists need to find drugs for all the other pathologies in the brains of dementia patients, as well?

“It’s the right time to focus on these tough questions,” Dr. Skovronsky said.

Gina Kolata writes about science and medicine. She has twice been a Pulitzer Prize finalist and is the author of six books, including “Mercies in Disguise: A Story of Hope, a Family’s Genetic Destiny, and The Science That Saved Them.” @ginakolata • Facebook

Source: Read Full Article