Physician-Artists Explore Compassion and Healing in Powerful Baltimore Museum Exhibit

What is compassion? How does one define healing? Is suffering necessary? What is the purpose of pain? These are not existential questions for medical professionals, especially over the past 2 years, when there has been an unprecedented increase in illness, trauma, and death.

“Healing and the Art of Compassion (and the Lack Thereof!),” an art exhibit at Baltimore’s American Visionary Art Museum (AVAM) that is on display through September 4, 2022, explores those themes through photographs, mixed-media displays, videos, paintings, and sculpture — many of them by physician-artists.

It was a purposeful choice. AVAM founder and curator Rebecca Alban Hoffberger has always included physicians and scientists among the self-taught artists she features in the museum, saying that they fall into the rubric of who she considers to be creative.

Doctors and scientists are representative of “visionary thinking made manifest,” she says. For many of the AVAM exhibitions she has curated over 27 years, she has directed the museum have had a strong focus on medical and scientific themes.

The current exhibition was designed in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic began. For Hoffberger, it was an accident of timing. “What we manifest tends to dovetail with what needs to be focused on,” she says.

After the show was delayed by the pandemic, Hoffberger chose to add elements that would reflect the pain and suffering that COVID-19 has inflicted, particularly on healthcare workers. An iconic piece from the show is Arthur Lopez’s three carved saints — a cleaning woman, nurse, and physician — each of whom is crowned with a coronavirus halo.

“Healing and Compassion” also references history through its texts and objects, such as a replica of a 17th-century plague mask, and essays on unsung genetics pioneer Rosalind Franklin, infection control, and zoonoses. It also highlights some of the more dubious chapters in medicine, such as the unjust and disproportionate committal of women to psychiatric facilities to treat “hysteria” and, more recently, the skyrocketing cost of insulin.

Hoffberger’s overarching view is that the world would be vastly improved if compassion were king. “Our aim is to point a healing way forward beyond fear, violence, greed, bullying, and the twisted need to feel superior to someone else — the malignant pantheon of anti-compassion forces that have always sought to divide and debase our common humanity,” she wrote in an essay for the exhibition.

Three physicians featured in the exhibit have all found their way to express these themes, and all very differently. Here’s how they harnessed their artistic voices and generated powerful expressions from the world of medicine.

A Hand Surgeon Finds Another Way to Heal

The idea for a show about compassion came about through photographer Jon Kolkin, MD, a former hand surgeon with a long history of humanitarian work with Health Volunteers Overseas. Kolkin, a Buddhist, had the fortune of meeting and eventually developing a friendship with the Dalai Lama, who, in 2018, asked him to help spread a message of compassion. “How could I say no to His Holiness?” Kolkin says.

In early 2019, Kolkin and Hoffberger, who had never met, struck up a conversation while stuck in Denver waiting for a flight to a conference in Aspen, they were both going to attend. The two discussed Kolkin’s idea, and Hoffberger thought it would be perfect for her last exhibition as curator.

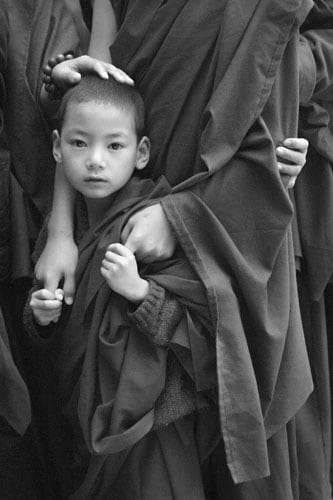

Hoffberger expanded on Kolkin’s initial proposal and then invited him to include a series of his oversized black and white photographs of Buddhist monks from his “Inner Harmony” series. Those photos also illustrate his book, Inner Harmony: Thriving in Balance. The book explores “core principles central to living a less stressful, more balanced life, regardless of one’s spiritual beliefs,” according to Kolkin’s website. Inner Harmony won gold at the Tokyo International Foto Awards and Silver at the International Photography Awards. Kolkin’s work has been shown in solo and group shows at galleries in California, Maine, North Carolina, Atlanta, and Chicago.

They were taken in 10 Asian countries over a 13-year period. The photos are beautiful in their simplicity. Kolkin prefers black and white because it elicits a “tendency to get lost, absorbed in the emotion of what’s going on.” The photos — such as one of a monk with a dog in his lap and another of a child with his head being lovingly cradled — are hung so that the viewer is almost eye-to-eye with the person or people portrayed. They are not formal or staged portraits, but somewhat candidly taken during his long sojourns at various monasteries.

In a striking image — used as the exhibition’s centerpiece (and shown here) — a small boy stares directly at the viewer. It is impossible to look away from his penetrating gaze. His small hands grasp a single finger of an adult enveloping him from behind. Another adult’s hand rests softly on the crown of the child’s head. It’s an atypical gesture in Asia because the head is considered sacred, says Kolkin.

“The simple fact that someone is putting their hand on top of this boy’s head means that they are family,” Kolkin says. The photo also reflects the Buddhist belief in the unity of heart and mind. “The hand on his heart, the hand on his head, they are interconnected. They are inseparable.”

Kolkin believes that compassion is one of the foundational principles of humanity. “Unless you’re a sociopath, if you see someone in pain, our instinct is to feel that we want to help,” he says.

For the last decade, Kolkin has been giving presentations on life balance and how everyone — from therapists to cancer survivors to medical students to physicians and nurses — can live a less stressful and compassionate life. One of the concepts he teaches is how to go from concern to effective action. That is, “how to navigate in a world where there is turmoil, whether it’s in the medical profession or for people in general, in such a way in that one is effective at being helpful for others while not causing harm for oneself.”

Emotional regulation and getting rid of biases and building perspective are key, says Kolkin. A simple strategy he shares with physicians: Put a hand on the doorknob before entering a patient room and take a moment to think about why you are there.

With the “Inner Harmony” series, he has been trying to communicate the eastern concept of compassion based on constructive positive emotions, he said. For physicians, it means accepting that though you may not have control over the situation, you do have control over your emotions.

A Neurosurgeon Explores Universal Suffering

One of the more visually overwhelming pieces in the AVAM show is a brightly colored, four-paneled painting by Nahum HaLevi, an acronym of Nathan Karl Moskowitz, MD, PhD, a neurosurgeon at Shady Grove Adventist Hospital in Rockville, Maryland. Each 48-by-60-inch panel is like a psychedelic fever dream with dozens of human characters, animals, reptiles, and celestial symbols. In one panel, a woman’s bulging belly holds what appears to be 10 fetuses; in another, a pox-covered bearded man is perched on a hill of dirt beneath a lollipop swirl of a sun.

His work is on permanent display at Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, in Jerusalem, and has been shown in Jewish Community Centers and galleries in the United States, Australia, and the Czech Republic. Moskowitz also had work exhibited at AVAM in 2007.

He said he was “overjoyed” at being selected by Hoffberger for the “Healing and Compassion” show. The theme was important to him, Moskowitz says. “Medicine is amazing, we do wonderful things, but look at COVID — out of the blue. This is the 21st century, and we’re dying like flies. That’s a lack of healing and a lack of compassion. From a divine universal point of view, how do you understand that?”

Moskowitz, 64, grew up in the Bronx and began painting in 1978 with a watercolor set given to him by his wife. By 1999, the self-taught artist had moved on to oil paints and the ambition to bring the entire Hebrew bible (Old Testament) to life on canvas to “create sort of a Jewish Sistine Chapel.”

The paintings at AVAM depict the Book of Job, which Moskowitz says fit in perfectly with the healing and compassion theme. The work attempts to answer the question of why bad things happen to good people. “Everybody will have something bad happen to them,” he says. “Nobody gets a perfect life. That’s just part and parcel of humanity, part and parcel of the laws of nature and the universe. You can accept them, not accept them, or you can have perseverance and patience like Job and ultimately get through it.”

Painting takes Moskowitz deep into pondering the meaning of the religious texts and the metaphysical. It is not relaxing but helps him process life and his medical practice. “As I think about all these biblical characters, it gives me an understanding of the human heart, the human brain, which does carry through to medicine and allows me to understand my patients more.”

A Pediatrician Plumbs the Depths of Hate

The exhibit also explores suffering and what Hoffberger perceives as what we get when compassion is lacking — a world of violence and extremism.

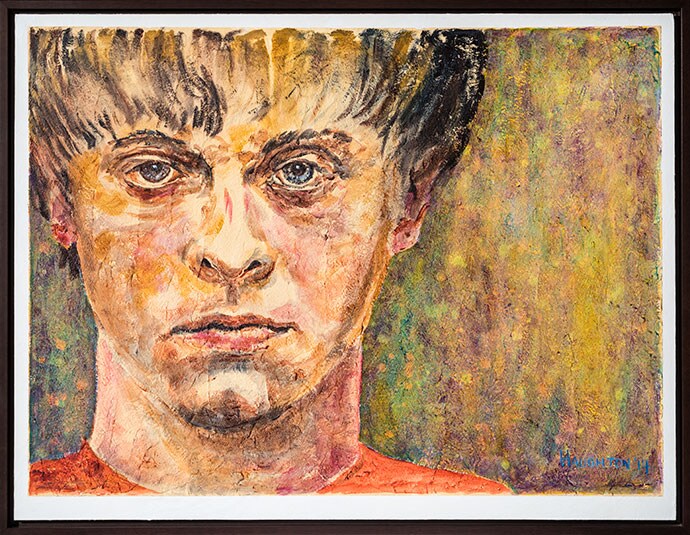

Vancouver, Canada–based David A. Haughton, MD, who no longer practices but specialized in pediatric emergency medicine, has been equally appalled by what he sees as a rise of supremacist movements. Three starkly realistic portraits from his “Angry White Men” series are in the exhibit: Dylann Roof (Mugshot XXIV, shown here), who, in 2015, at the age of 21, murdered 9 people in a church in Charleston, South Carolina, in a racially-motivated hate crime; Anders Behring Breivik, a far-right Nazi admirer who, in 2011, killed 77 people in a bombing in Oslo and a shooting at a Norwegian summer camp; and James Alex Fields, who drove his car into peaceful counter-protesters at a white supremacy rally in 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia, killing Heather Heyer and injuring several dozen others.

The self-taught Haughton is not pessimistic by nature. He had somewhat of an idyllic childhood split between Greece — where he first took up drawing as a 14-year-old — and Philadelphia, where his mother was a pediatrician and child psychiatrist and his father was an Episcopalian minister. He practiced medicine until 2017, when he decided to try out a career as a full-time artist.

Haughton is an accomplished landscape painter and calls those his “happy paintings.” But a dominant theme in his other work is evil. It reflects what he describes as a constant dialogue with God. Early in his career, as a resident in a cancer ward in a Los Angeles children’s hospital, he came to believe that “the cutest kids with the nicest families have the worst prognosis.” It led him to question God.

In response, Haughton produced a dark and disturbing series of more than 100 paintings and etchings, the “Kindertotentanz,” some of which were previously displayed at AVAM. In an essay on the series, he said “the anger and helplessness I felt compelled me to begin the ‘Kindertotentanz,’ an ongoing series of works that express my ambivalence with modern medicine.”

Haughton began the “Angry White Men” series in 2017 in reaction to what he felt was a rise of extremism across the globe fuelled in part by the election of Donald J. Trump as US President. He chose subjects whose images were easily found on the internet; unfortunately, he has found, and continues to find an endless parade of subjects for his portraits.

Art Reflecting Life — in Medicine

Medicine “gave me insight, and a clear, not vision, but a spectacle of great pain,” says Haughton. Painting gives him more of an avenue to explore his questions about good and evil.

He found a lack of compassion in the US healthcare system, he says, adding that he spent too much of his time fighting politics. In Canada — where he moved with his first wife — he became a much better pediatrician, inspired by what he called Canadians’ bigger hearts and larger empathy centers.

Moskowitz, too, believes there’s a lack of compassion in US medicine, but that the fault lies in the system.

The majority of people go into medicine “because they have compassion,” he says. Even the most idealistic, compassionate young people will become frustrated by the system. Not every physician finds art as an outlet, but at those times every doctor has to remember what inspired them in the first place: “You really have to love medicine.”

Alicia Ault is a Lutherville, Maryland–based freelance journalist whose work has appeared in publications including JAMA, Smithsonian.com, The New York Times, and The Washington Post. You can find her on Twitter @aliciaault.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Source: Read Full Article