For Florida, the coronavirus pandemic was a perfect storm

If there’s one state in the U.S. where you don’t want a pandemic, it’s Florida. Florida is an international crossroads, a magnet for tourists and retirees, and its population is older, sicker and more likely to be exposed to COVID-19 on the job than the country as a whole.

When the coronavirus struck, the conditions there made it a perfect storm.

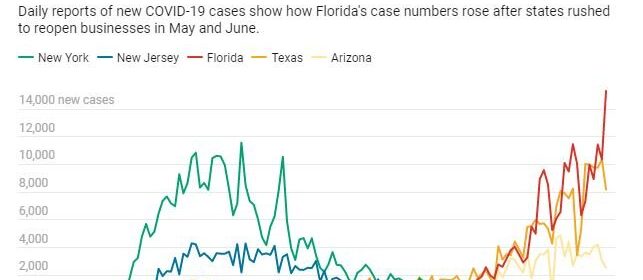

Florida set a single-day record for new COVID-19 cases in early July, passing 15,000 and rivaling New York’s worst day at the height of the pandemic there. The state has become an epicenter for the spread, with over 300,000 active cases. Its hospital capacity is under stress, and the death toll has been rising.

Despite these strains, Disney World reopened two theme parks on July 11, and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced schools would reopen in August. The governor had ordered bars to close in late June as case numbers skyrocketed, but he hasn’t made face masks mandatory or moved to shut down other businesses where the virus can easily spread.

As public health researchers, we have been studying how states respond to the pandemic. Florida stands out, both for its absence of statewide policies that could have stemmed the spread of COVID-19 and for some unique challenges that make those policies both more necessary and more difficult to implement than in many other states.

The challenges of economic pressures

Florida is one of nine states with no income tax on wages, so its tax base relies heavily on tourism and property in its high-density coastal areas. That puts more pressure on the government to keep businesses and social venues open longer and reopen them faster after shutdowns.

If you look closely at Florida’s economy, its vulnerabilities to the pandemic become evident.

The state depends on international trade, tourism and agriculture—sectors that rely heavily on lower-wage, often seasonal, workers. These workers can’t do their jobs from home, and they face financial barriers to getting tested, unless it’s provided through their employer or government testing sites. They also struggle with health care—Florida has a higher-than-average rate of people without health insurance, and it chose not to expand Medicaid. In the tourism industry, even young, healthy employees typically at lower risk from COVID-19 can unknowingly spread the virus to visitors or vice versa.

The past few weeks have been emblematic of the economic battles facing a state that depends on tourism for both jobs and state revenues.

Even as the public health risks were quickly rising, businesses continued to open their doors. Major cruise lines planned to resume their itineraries as early as September. A note on the Universal Studios website read: “Exposure to COVID-19 is an inherent risk in any public location where people are present; we cannot guarantee you will not be exposed during your visit.”

Reopening guidance has been largely ignored

The Governor’s Re-open Florida Taskforce issued guidelines in late April meant to lower the state’s coronavirus risk, but those guidelines have been largely ignored in practice.

No county in Florida has reduced cases or maintained the health care resources recommended by the task force. The data needed to fully assess progress are also questionable, given a recent scandal regarding the state data’s accuracy, availability and transparency.

Still, the coronavirus’s rapid surge in Florida is evident in the state-reported cases. Testing lines are long, and almost 1 in 5 tests have been positive for COVID-19, suggesting the prevalence of infections is still increasing.

Florida’s patchwork of local rules also makes it hard to contain the virus’s spread.

With no statewide mask rules or plans to reverse reopening, other than for bars, communities and businesses have taken their own actions to implement public health precautions. The result is varying mask ordinances and restrictions on large gatherings in some cities but not those surrounding them. Though the Florida Department of Health has issued an advisory recommending face coverings, some local areas have voted down mask mandates.

More warning signs ahead

Late summer and fall will bring new challenges for Florida in terms of the virus’s spread and the state’s response to it.

That’s when Florida’s risk of hurricanes grows, and while Floridians are well-versed in hurricane preparedness, storm shelters aren’t designed for social distancing and will need careful plans for protecting nursing home residents. Storm cleanup could mean lots of people working in close proximity while protective gear is in short supply.

If Florida’s schools reopen fully, the risk of the virus rapidly spreading to teachers, parents and children who are more vulnerable is a real concern being weighed against the costs of keeping schools closed.

Colleges that reopen to classes and sporting events also raise the risk of spreading the virus in Florida communities. And the possible return of retirees who spend their winters in Florida would increase the high-risk population by late fall. One in five Florida residents is over age 65, giving the state one of the nation’s oldest populations—a risk factor, along with chronic illnesses, for severe symptoms with COVID-19.

Florida is also a battleground state for the upcoming presidential election, and that’s likely to mean campaign rallies and more close contact. The Republican National Convention was moved to Jacksonville after President Donald Trump complained that North Carolina might not let the GOP fill a Charlottesville arena to capacity due to coronavirus restrictions. Florida organizers recently said they were considering holding parts of the convention outdoors.

Source: Read Full Article