Door to Door in Miami’s Little Havana to Build Trust in Testing, Vaccination

Little Havana is a neighborhood in Miami that, until the pandemic, was known for its active street life along Calle Ocho, including live music venues, ventanitas serving Cuban coffee and a historic park where men gather to play dominoes.

But during the pandemic, a group called Healthy Little Havana is zeroing in on this area with a very specific assignment: persuading residents to get a coronavirus test.

The nonprofit has lots of outreach experience. It helped with the 2020 census, for example, and because of the pandemic did most of that work by phone. But this new challenge, community leaders say, needs a face-to-face approach.

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KHN’s free Morning Briefing.

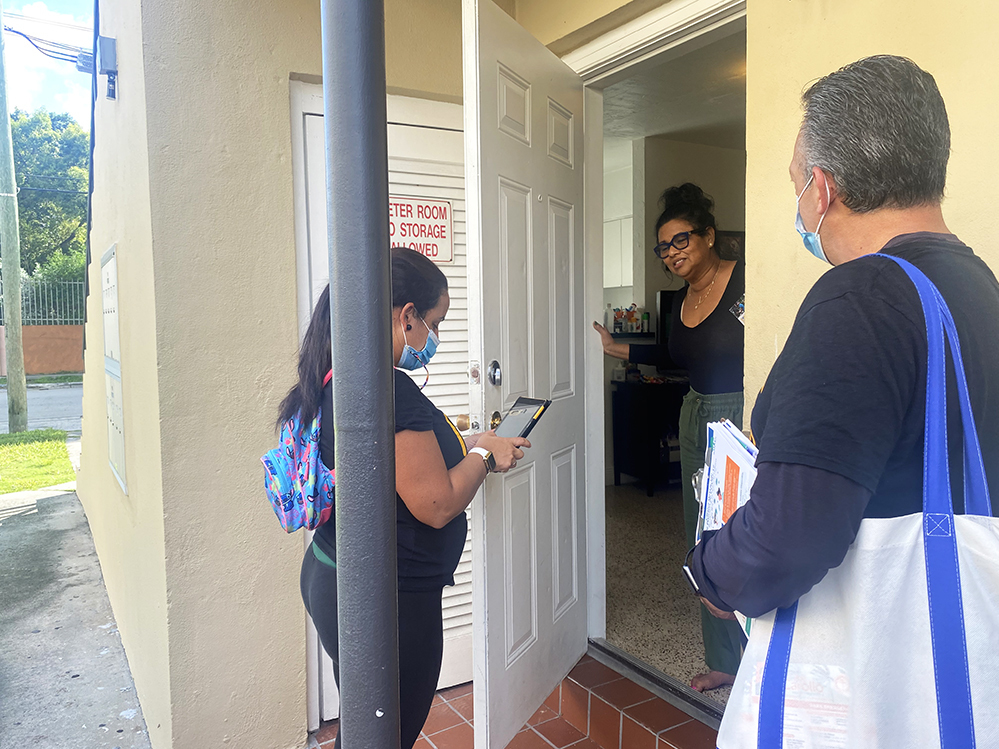

The group’s outreach workers have been heading out almost daily to walk the quiet residential streets, to persuade as many people as possible to get tested for covid-19. On a recent afternoon, a group of three — Elvis Mendes, María Elena González and Alejandro Díaz — knocked on door after door at a two-story apartment building. Many people here have jobs in the service industry, retail or construction; most of them aren’t home when visitors come calling.

Lisette Mejía did answer her door, holding a baby in her arms and flanked by two small children.

“Not everyone has easy access to the internet or the ability to look for appointments,” Mejía replied, after being asked why she hadn’t gotten a test. She added that she hasn’t had any symptoms, either.

The Healthy Little Havana team gave her some cotton masks and told her about pop-up testing planned for that weekend at an elementary school just a short walk away. They explained that people might lack symptoms but still have the virus.

Testing Is Still Too Difficult

The nonprofit organization is one of several receiving funding from the Health Foundation of South Florida. The foundation is spending $1.5 million on these outreach efforts, in part to help make coronavirus testing as accessible and convenient as possible.

A number of social and economic reasons make it difficult for some Miamians to get tested or treated, or isolate themselves if they are sick with covid. One big problem is that many people say they can’t afford to stay home when they’re sick.

“People usually rather go to work than actually treat themselves — because they have to pay rent, they have to pay school expenses, food,” said Mendes.

This part of Miami is home to many Cuban exiles, as well as people from all over Latin America. Some lack health insurance, while others are undocumented immigrants.

So Mendes and his team try to spread the word among residents here about programs like Ready Responders, a group of paramedics that now has foundation funding to give free coronavirus tests at home in areas like this one, regardless of immigration status.

“Our mission is for all these people to get tested — regardless if they have a symptom or not — so we can diminish the level of people getting covid-19,” Mendes said. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, people who are infected but presymptomatic or asymptomatic account for more than 50% of transmissions.

The Health Foundation of South Florida’s coronavirus-related grants have ranged from $35,000 to $160,000; other recipients include the South Florida chapter of the National Medical Association, Centro Campesino and the YMCA of South Florida.

The foundation is focusing on low-income neighborhoods where some residents might not have access to a car or be able to afford a coronavirus test at a pharmacy. Their focus includes residential areas near agriculture work sites. In Miami-Dade County, the foundation is working with county officials directly to increase testing. In neighboring Broward County, the foundation is collaborating with public housing authorities to bring more testing into people’s homes.

Soothing Fears, Offering Options in Spanish

It’s time-consuming to go door to door, but worthwhile: Residents respond when outreach teams speak their language and make a personal connection.

Little Havana resident Gloria Carvajal told the outreach group that she felt anxious about whether the PCR test is painful.

“What about that stick they put all the way up?” Carvajal asked, laughing nervously.

González jumped in to reassure her it’s not so bad: “I’ve done it many times, because obviously we’re out and about in public and so we have to get the test done.”

Another outreach effort is happening at Faith Community Baptist Church in Miami. The church hosted a day of free testing back in October, with help from the foundation.

“You know us. You know who we are,” said pastor Richard Dunn II. “You know we wouldn’t allow anybody to do anything to hurt you.”

Dunn spoke recently in nearby Liberty City, a historically Black neighborhood, at an outdoor memorial service for Black residents who have died of covid. To convey the magnitude of the community’s losses, hundreds of white plastic tombstones were set up behind the podium. They filled an entire field in the park.

“Thousands upon thousands have died, and so we’re saying to the Lord here today, we’re not going to let their deaths be in vain,” Dunn said.

Dunn is also helping with a newly launched effort to build trust in the covid vaccines among Black residents, by participating in online meetings during which Black church members can hear directly from Black medical experts. The message of the meetings is that the vaccines are safe and vital.

“It’s taken over 300,000 lives in the United States of America,” Dunn said at the end of the meeting. “And I believe to do nothing would be more of a tragedy than to at least try to do something to prevent it and to stop the spreading of the coronavirus.”

Churches will play a big role in the ongoing outreach efforts, and Dunn is committed to doing his part. He knows covid is an extremely contagious and serious disease — this past summer, he caught it himself.

This story comes from a reporting partnership that includes WLRN, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Source: Read Full Article