Do local lockdowns stop the spread of covid?

In many areas under local lockdown, cases and hospital admissions have continued to soar. Does that mean restrictions don’t work?

Consider the national lockdown in the spring. While it feels like it was one single policy, it was in fact a package of different measures. Schools, universities and offices shut. Pubs, restaurants and non-essential shops closed. No-one could mix with people from outside their household. People were advised not to use public transport and to limit the number of times they visited essential shops.

Together these had a dramatic impact on cases, and the number of coronavirus patients in hospital plummeted from 20,000 to about 800.

- Postcode lookup: Check the rules in your area

How much each part of that lockdown contributed is hard to say.

The rules were relaxed but then, at the end of June, Leicester became the first place to go into a local lockdown. Other cities, and whole regions, have followed. But so far, Leicester’s lockdown is the only one to have come close to the strictness of the national policy. Shops and pubs were stopped from opening. Households were barred from mixing indoors. And new cases of the virus dropped by 60% during July. People in hospital beds with coronavirus fell from 88 to 18.

- Leicester marks 100 days of extra restrictions

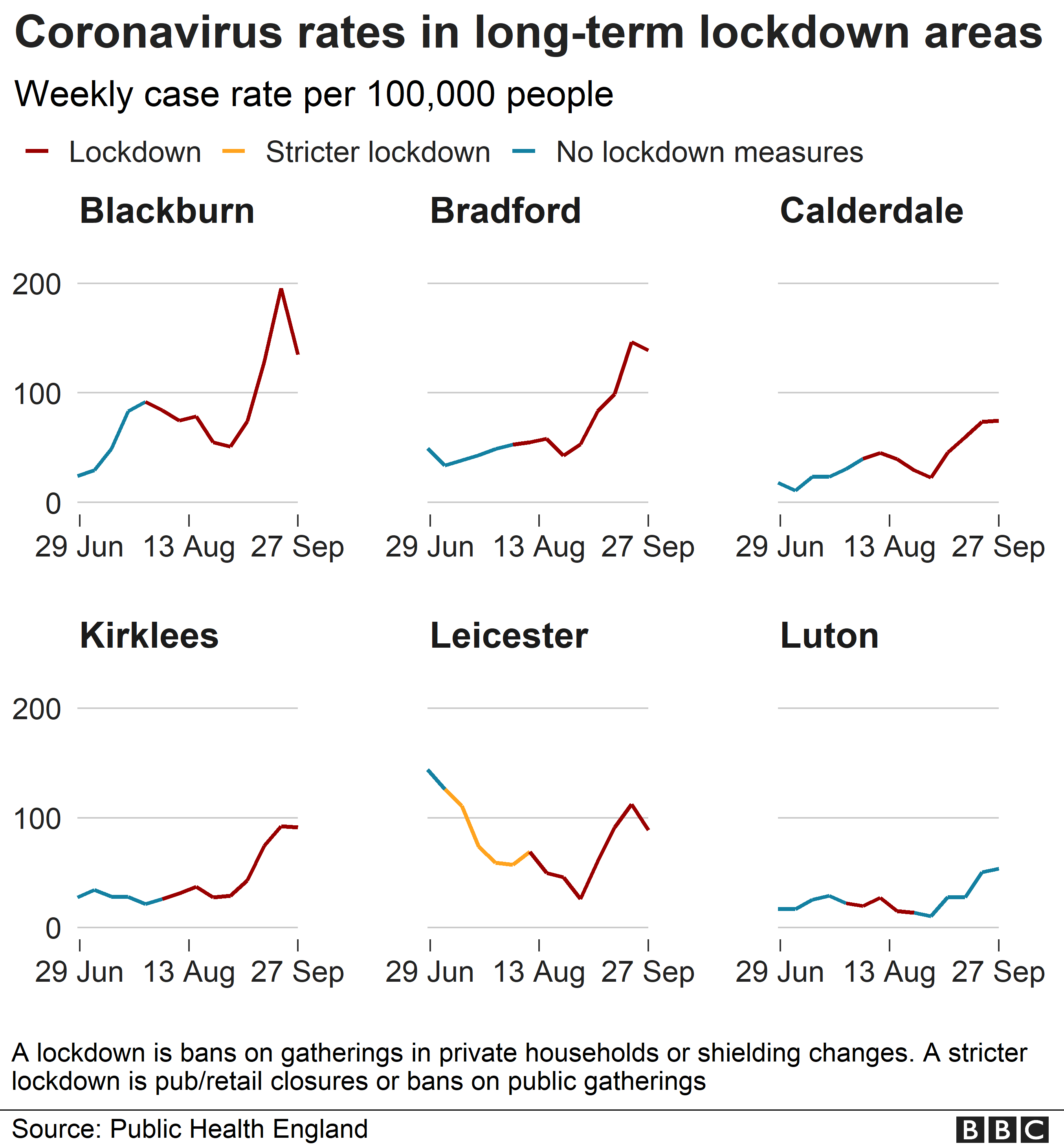

Since Leicester, local lockdowns have multiplied. More than 15 million people – very roughly, a quarter of the UK population – have come under new curbs, in some form.

And it’s become harder to see whether they are working or not.

Take Bolton, in Greater Manchester…

- At the end of July, households were banned from mixing indoors

- In August, leisure and entertainment venues were prevented from opening, as they reopened nationally

- In September, all food outlets became takeaways and a curfew was introduced

After the first changes, cases continued to rise, throughout August. Then, after pub and restaurant closures, case rates dropped sharply. It is, however, too soon to say for sure that the stricter measures led directly to the decline.

In the rest of Greater Manchester, gatherings with other households were banned but shops, pubs and restaurants remained open. Cases have mostly kept climbing throughout these local restrictions.

However, the latest week’s data will be welcome news – suggesting the sharp increases might be levelling off. The rise in cases in many areas under local lockdown appears to be slowing, in line with the national picture.

This may be a sign that the England-wide “rule of six” is working.

A large national study, published last week, confirmed the growth in cases was slowing across England, although overall levels remained high. But restrictions on households meeting – which have been seen at a local level – don’t always lead to a slowing case rate. And this change in impact highlights the many factors involved which make it difficult to isolate the precise effect of local lockdowns.

People don’t necessarily change their behaviour exactly in line with rule changes.

When concerns about cases rising begin to be reported, some people alter their behaviour before any law change. Other people, even when the rules come into place, don’t obey them.

So it may be a question of timing: are people more ready to restrict their movements now than they were in August?

To complicate the figures further, other things have been going on at the same time as local lockdowns were being introduced, including summer holiday season and schools reopening.

In Leicester, cases fell when restrictions were introduced. When they were progressively eased in August and September, cases started to rise. But this rise coincided with more people travelling abroad. And with children going back to school.

In Greater Manchester, cases also rose over those months despite the area being in lockdown – albeit a looser version than Leicester’s had been.

Unpicking these different factors is a big challenge.

Looking at “positivity rates” – the proportion of all tests that are positive, adjusting for different levels of testing – shows there have been increases in cases across England, with particularly sharp spikes in the North West and North East between the end of August and the end of September. Restrictions in those regions were only introduced between the middle of September and the beginning of October, making it too soon to see the impact of these rules.

But in Blackburn, which has been in lockdown long enough for an effect to be seen, there was also a rise in cases – though this has come back down in recent weeks.

Recent increases in hospitalisations from coronavirus have highlighted the extent of the challenge facing the north of England. Though without up-to-date localised data, it is difficult to judge whether the impact on a local level – such as those in Blackburn – have helped prevent serious cases.

There’s no doubt the national lockdown had a considerable impact on cases.

Fundamentally, the virus needs people to be in close contact and mixing between circles to spread through the population. How tight the restrictions are makes a difference – look at the experience of Leicester, compared with Oldham or Blackburn.

But so do the crucial issues of timing and compliance. A lockdown only works if people stick to it.

The data also indicates that any impact lockdowns do have is far from permanent – relax the restrictions and allow more contact, and the virus will quickly start to spread again.

Unless and until a viable vaccine becomes available, government will be faced with the same choice: shut down large chunks of society or allow the virus to tear through communities, with little idea of the true toll that either will exact.

In many areas under local lockdown, cases and hospital admissions have continued to soar.

- SOCIAL DISTANCING: How have rules on meeting friends changed?

- SYMPTOMS: What are they and how to guard against them?

- LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

- SOCIAL LIFE: The rules when I go to the pub?

- Blackburn

- Coronavirus lockdown measures

- Coronavirus pandemic

- Coronavirus testing

- Leicester

Source: Read Full Article