HPV and Cervical Cancer

Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection of the uterine cervix can lead to cervical cancer in a small percentage of cases. HPV infection is usually cleared from the body by the immune system within approximately two years. Persistent or recurrent infection may lead to the development of cervical cancer.

Prevalence of cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is the fourth most frequent cancer in woman. In 2012 there were about 530,000 new cases of cervical cancer globally. It accounts for about 270,000 deaths each year, which comes to around 7.5% of all female cancer deaths. In the UK, for example, over 3000 women are diagnosed with this cancer each year. However, the majority of patients with the disease, namely 85%, come from less developed countries. The global mortality rate for cervical cancer is high at 52%.

Risk factors for the disease

Cervical cancer is not a hereditary disease. The cancer develops as a consequence of HPV infection, following the transmission of oncogenic strains of the virus. This may occur through skin-to-skin contact in the genital areas of the vagina, anus or through the mouth or throat.

Cervical cancer can take several years to become established. In general, it takes about 15-30 years for the cancer to develop in an individual with a robust immune system. If the immune status is compromised, as in a person with HIV infection, for example, this time may be as short as 5-10 years. It is the most common cancer in women under the age of 35

Other risk factors for the disease include:

- weakened immunity,

- Early age at first sexual intercourse

- Smoking

- multiple sexual partners

- higher number of children

- long-term use of oral contraceptives

- chronic cervical inflammation

Pathogenesis of the disease

HPV infection leads to the takeover of the epithelial cell by the virus, with expression of two proteins called E6 and E7. These interfere with the normal cell regulatory functions, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation and inhibition of programmed cell death (apoptosis) at the end of its life cycle. Usually, such infected cells are removed by the immune system. If not, persistent infection leads to mutations in the cellular genes which promote greater proliferation. The end-result is precancerous changes, and finally frank cancer.

Cancer-forming HPV strains

A dozen strains of HPV have been identified to be associated with future cervical cancer risk. Almost all cervical cancers have been found to follow HPV infection. However, about 70% of all cervical cancers are caused by HPV types 16 and 18. Two vaccines have been developed to protect against infection by these particular strains. One of the vaccines also protect against some forms of warts which develop through infection with types 6 and 11. These vaccines are most effective when administered at the age of 11-12 years to girls who have not yet engaged in sexual intercourse of any kind.

Symptoms of the disease

In the early stages there are no real signs of the disease. As the disease progresses symptoms appear, such as:

- Vaginal bleeding at unusual times. This refers to bleeding outside the period of menstruation for women of child-bearing age, and at any time after women have been through the menopause.

- Pain and discomfort during sex

- Unusual-smelling vaginal discharge

- Constipation

- Fatigue

- Blood in urine

- Incontinence

- Swelling of one leg

- Kidney pains in the side or back

- Weight loss

- Loss of appetite

- Bone pain

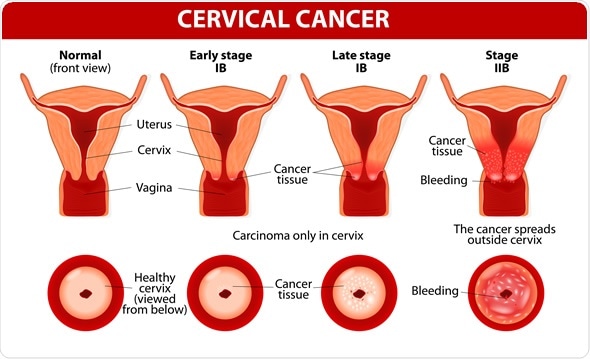

Where the cancer forms

The cervix is the slim section which makes up the opening of the uterus into the vagina, or birth canal.

Cervical cancer forms when an oncogenic HPV virus transforms cells in the cervix into abnormal cells by inducing alterations to their deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or ribonucleic acid (RNA). The ectocervix is the part of the cervix which faces the vagina. It is lined by a layer of epithelium. It is continuous with the cervical canal, lined by glandular epithelial cells. This is also called the endocervix. The meeting point between the ectocervical and endocervical cells is called the transformation zone. Cells in this transformation zone are most likely to become cancerous.

Screening for cervical cancer

When cervical cancer screening is carried out, professionals examine cells retrieved from the ectocervix through a smear test for suspicious changes in them. If there are mild signs of abnormality, the patient is advised to come in for regular monitoring. If more severe abnormalities are detected, the patient may be advised to undergo a colposcopy where the cervix can be visually and microscopically analyzed to identify the type and severity of the lesion, whether benign, precancerous or cancerous.

The three tests commonly used for cervical cancer screening include:

- HPV testing of cervical cell samples to identify the presence of DNA or RNA from high-risk strains of virus, even without visible or microscopic cell changes

- Conventional testing (Pap/smear tests) and liquid-based cytology

- Visual inspection

HPV testing in cervical cancer screening is indicated for:

- Women who had abnormal Pap tests and require follow-up for confirmation

- Women over the age of 30 years who also have a Pap test done

- Women over the age of 25 years

References:

- World Health Organization fact sheet on cervical cancer: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs380/en/

- Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust on cervical cancer and the cervix: http://www.jostrust.org.uk/about-cervical-cancer/the-cervix

- http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-fact-sheet

Further Reading

- All Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Content

- What is HPV?

- HPV Prevention

- HPV and Lung and Throat Cancer

- HPV and Warts

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019

Written by

Deborah Fields

Deborah holds a B.Sc. degree in Chemistry from the University of Birmingham and a Postgraduate Diploma in Journalism qualification from Cardiff University. She enjoys writing about the latest innovations. Previously she has worked as an editor of scientific patent information, an education journalist and in communications for innovative healthcare, pharmaceutical and technology organisations. She also loves books and has run a book group for several years. Her enjoyment of fiction extends to writing her own stories for pleasure.

Source: Read Full Article